This is the first in a series of blog posts where I take a detailed look at how you can invest in quality dividend stocks for long-term income and growth.

Every journey begins with the first step, and in this case, the first step is to decide if dividend stocks are the right choice for you.

This will depend on what you’re after in terms of income and growth, as well as what risks you’re willing to accept in terms of liquidity (how easily you can get your money - your capital - back) and volatility (how much your income and capital could go up or down).

To explain all this, I’ll compare the pros and cons of dividend stocks with the pros and cons of high-interest savings accounts, and by the end, you’ll have a better idea of whether or not dividend stocks are right for you.

Table of contents

- The pros and cons of instant access savings accounts

- The pros and cons of fixed-term savings accounts

- The pros and cons of investing in dividend stocks

- Conclusion: Savings vs. dividends, who wins?

The pros and cons of instant access savings accounts

Let’s start with perhaps the simplest way to build a passive retirement income: the trusty old instant-access savings account.

I imagine you have at least one of these accounts already, probably with the same bank as your current account.

These accounts are very simple, and they have a number of features that will help you put the pros and cons of dividend stocks into context.

Pro #1: Your capital is not at risk

This is probably the key difference between saving and investing for most people. If you put £100,000 into a savings account, you know (short of nuclear war) that you can get your £100,000 back when you want it.

In theory, your money isn’t entirely safe. The government only guarantees savings up to £85,000, so if you have more than that with one bank and it goes bust, you may not get all your money back.

However, as the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank shows, governments are unlikely to allow customers of any major bank to lose money because the resulting fear might spark a series of bank runs that could decimate the entire banking system.

So, in practice, the odds of losing any money in a savings account must be close to zero, but if you’re still worried, you can, of course, limit yourself to saving no more than £85,000 with any one institution.

Pro #2: You can get your money back instantly

As well as not having to worry about losing any money, you can also pull your money out of an instant-access savings account whenever you like (it’s in the name, after all).

This is useful if you’re saving up for Christmas, a birthday or something else relatively short-term or if you’re using the account as an easy-access safety net in case you lose your job. But if you’re using savings to build or generate a retirement income, having instant access to the savings is less useful.

In fact, instant access can be problematic because some people will be tempted to draw down their savings to spend on whatever whizzy thing catches their attention, and spending your savings is not a good way to build your retirement income. This is precisely why pensions lock up your money until you’re 55.

Con #1: Your income will be low

A quick scan of instant access savings accounts on MoneySuperMarket shows me that you could get a 3.55% income from an account provided by Chip, which is a company I’ve never heard of.

If I look down the list for a company I have heard of, then it seems you can get a 3.2% income from Sainsbury’s Bank.

However, to get that rate, you have to promise not to make more than three withdrawals in a given year, which they call a defined access account, so it isn’t really instant access.

Marcus (from Goldman Sachs, no less) will give you a 3.2% income on anything up to £250,000, so for each £100,000 you save with them, you’ll get a nice £3,200 income.

These rates are much higher than the rates that were available for most of the last decade, as higher interest on our savings is one of the few benefits of higher inflation.

Even so, they are still paltry. The Bank of England’s inflation target is 2%, so if your savings account is paying 3.2%, then more than half of that will be eaten up by inflation, leaving you with a real (inflation-adjusted) income of 1.2%, which barely seems worth the effort.

Con #2: Your income could go down

Another downside to instant access savings is that the paltry income is also variable. So, if the Bank of England lowers interest rates (which seems unlikely anytime soon), then the already unimpressive income from your savings will become even less impressive.

Let’s not forget that even the best instant access savings account in 2021 had an interest rate of less than 1%, so there is a serious risk that the income from an instant access savings account could fall very close to zero, which isn't great if you're trying to live off that income.

Con #3: Your income and capital aren’t protected from inflation

The upside of savings accounts is that the numerical value of your capital doesn’t go up or down unless you add or withdraw funds. As I said earlier, if you put in £100,000, you can always get £100,000 back out again (barring a total collapse of the banking system).

But this works both ways. If you put in £100,000 and if inflation runs at 5% for the next five years, the purchasing power of your savings (the amount of stuff you can buy with it) will have gone down by about 25%. As your interest is calculated as a percentage of your savings, the purchasing power of your income will have declined as well.

Over many years and (hopefully) decades of retirement, this can seriously erode the living standard of retirees.

Okay, here's a quick summary before we move on to fixed-term savings accounts:

Instant access savings accounts give you: (1) the simplicity of instant access, (2) effectively zero capital risk, (3) a low and variable income and (4) no inflation protection.

If you want to do better than that, then you have to give something up, and most long-term savers are willing to give up what they don’t need, which is instant access.

The pros and cons of fixed-term savings accounts

Fixed-term or fixed-interest savings accounts give banks and other financial institutions access to your savings for a fixed period of time, which allows them to lend that money to other customers, also for a fixed period. So, a bank effectively borrows money from you for, say, three years, knowing it can lend that money to a person or a business for two years.

This is called borrowing long and lending short, and it’s one of the safest ways to run a lending institution. It's definitely much safer for a bank than borrowing money through instant access current accounts and savings accounts, where nervous depositors can pull their money at a moment's notice, as Northern Rock and Silicon Valley Bank found out to their detriment.

For the most part, fixed-term savings accounts are very similar to instant access savings accounts, but there are some differences.

Pro #1: Your capital is not at risk

This is exactly the same as the instant access accounts. You put your money in, the government explicitly guarantees the first £85,000 (and perhaps implicitly guarantees the rest), and you can get all your money back, although, of course, you can only get it back after a certain amount of time, which is usually one to five years.

Pro #2: Your income will be higher

On MoneySuperMarket’s list of fixed-rate accounts, Paragon Bank is offering 4.35% interest on anything up to £500,000. You can’t access your money for two years, but of course, that shouldn’t be a problem if you’re saving for your retirement.

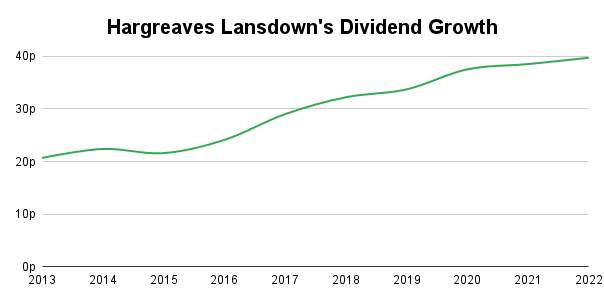

On Hargreaves Lansdown’s savings platform, known as Active Savings, you can get a 4.5% income on your savings through a 2-year fixed-interest account with Close Brothers Bank.

That’s quite a jump up from the 3.2% interest rate on the instant access account from Marcus. It means that for every £100,000 you put into that account, your income would be 41% higher with Close Brothers than with Marcus (£4,500 versus £3,200). That’s a lot more income for not a lot more effort.

Pro #3: Your income won’t go down

Unlike instant access accounts, which usually have variable interest rates, fixed-term savings accounts have fixed interest rates, so for each year that your money is locked up, you’ll know exactly how much income you’ll get.

This is a big deal for many retirees, and this is the main reason why my parents opted for a combination of annuities and fixed-interest savings when they retired. They valued knowing exactly how much they would receive each year over the potentially higher income they could get by investing some of their nest egg into dividend-paying shares.

Con #1: Your capital will be locked up for years

Fixed term means no instant access, but this isn’t necessarily a problem if you’re interested in building up or living off your retirement savings. And if you do think you might need a lump sum fairly soon, just don’t put that money into a fixed-term savings account.

Con #2: Your income and capital aren’t protected from inflation

As with instant access accounts, the certainty that comes with savings (in this case, the certainty of income and capital) is a double-edged sword because it provides no protection from inflation.

By removing any volatility from your income and capital, you remove uncertainty, but you also lock in the certainty that the purchasing power of your income and capital will be eroded by inflation.

So, to summarise the ups and downs of fixed-term savings, they give you: (1) an income that is both higher and more reliable than instant access accounts; (2) no capital risk other than from inflation; (3) no instant access, which shouldn't be a problem for long-term savers.

The pros and cons of investing in dividend stocks

There are some very significant differences between dividend stocks and savings accounts, but there are also some similarities. To make sure we’re on the same page, I'll focus on the similarities first.

Dividend stocks and the savings account analogy

Perhaps the easiest way to think about dividend stocks is to think of them as a special type of savings account (this is a bit of a stretch, but I find the analogy useful).

To begin with, when you buy shares in a company, you are, in fact, becoming a shared owner of that business, along with all the other shareholders. So, if a company has 100 shares and you buy one share, you now literally own 1% of that company.

And what do you get if you own shares in a business? You get a proportional share of its profits, that’s what. In the previous example, you own 1% of the company's shares, so you are now entitled to 1% of its profits.

This is where your income as a shareholder comes from. You invest in a company, the company makes a profit, and that profit belongs to you (proportional to how many shares you own).

One slightly complicating factor is that the income yield you get from your investment depends not only on how much profit the company makes but also on the price you pay for its shares.

For example, let’s say we have a company that earns a profit of £100 million per year. It also has 100 million shares, so it earns £1 per share.

Let’s also say that the share price is £10. This gives the shares an earnings yield (which is approximately equivalent to the interest rate on a savings account) of 10%.

The odds of you finding a savings account with a 10% interest rate are pretty close to zero, but there are, in fact, quite a few UK dividend stocks that have earnings yields of well over 10%. I’ll let that sink in for a moment.

However, unlike a savings account, where you can withdraw your income and spend it as you like, you can’t just withdraw all of the income (the profits) generated by a company just because you own some of its shares.

Instead, once or twice each year (dividends are usually paid twice per year), management will decide how much of the company's earnings it wants to retain within the business to fund investments in new factories, vehicles, shops, inventory and so on. Any earnings which aren’t needed to drive growth are then paid out to shareholders as dividends.

Let’s go back to the previous example.

The company earns £1 per share (£100m in total). Management decides to retain half of that within the business to drive growth, so 50p per share (£50m) is retained, and 50p per share (£50m) is paid out to shareholders as dividends.

In this example, the dividend is covered twice over by earnings. This is known as the dividend cover ratio, and a cover of two times is fairly typical.

The retained earnings fund new assets which are productively employed to generate higher profits. So, a year later, thanks to this additional investment, the company earns £105 million, or £1.05 per share. Once again, management pays out half of the earnings as a dividend, so the dividend grows from 50p to 52.5p, a 5% increase.

This is how companies are able to pay out an income while growing that income along with their capital value.

To put this into savings account terms, it’s like having a savings account that pays 10% interest. If you put in £100, you’ll get £10 interest at the end of the year. If you put £5 of that interest back into the account, you’ll have £5 of cash to spend and £105 left in the account. Next year, because you have 5% more in the account, the interest will go up by 5% to £10.50. In this way, you have a good cash income that also grows ahead of inflation.

Hopefully that’s reasonably clear, so let’s move on to the pros and cons of dividend stocks.

Pro #1: Your income could be very high

Just as different savings accounts have different interest rates, different dividend stocks have different earnings yields. However, on average, dividend stocks have earnings yields that are far higher than the interest rate on savings accounts.

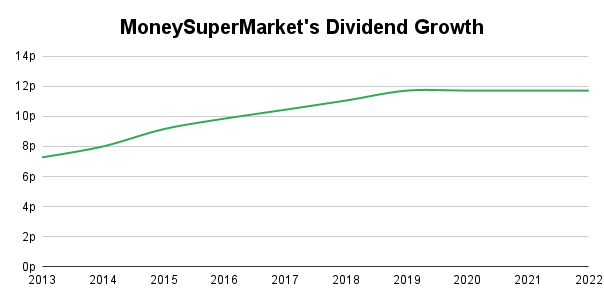

For example, MoneySuperMarket, which I mentioned above, is one of 23 holdings in my dividend portfolio.

As I write, it has a share price of £2.49 and normalised earnings (an estimate of what the company would earn in a “normal” year) of 16p, giving the company a normalised earnings yield of 6.2%.

That isn’t quite the 10% level I used as an example above, but it’s a lot better than the 4.5% on offer from Close Brothers’ 2-year fixed-term savings account.

MoneySuperMarket’s dividend yield is currently 4.7%, so that’s 4.7% paid out to me as a shareholder and another 1.5% retained within the business to help it grow.

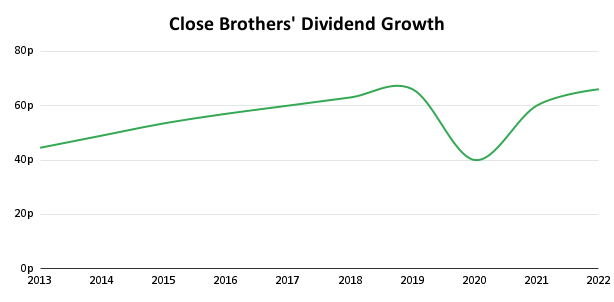

As for Close Brothers, I do have some money in their fixed-term savings accounts, but I also own shares in the company as well.

Close Brothers has seen its share price fall almost 50% over the last two years due to a number of factors, including fears about a potential recession, problems at Close Brothers with an acquired business and more recently, problems at Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse.

Today, the share price is £8.53, and I estimate Close Brothers’ normalised earnings to be about £1.50 per share, giving it a very high normalised earnings yield of 17.6%.

That income isn’t guaranteed (a downside to dividend stocks that I’ll cover shortly), but it is still very attractive.

Close Brothers’ dividend yield is 7.7%, so as things stand today, I’m getting a 7.7% cash income plus another 9.9% of income which management reinvests back into the “account” (i.e. the business) on my behalf to fuel even higher dividends in the future.

Last but not least, I mentioned Hargreaves Lansdown earlier for its Active Savings platform, but I also use it for ISAs and SIPPs, and on top of that, I own shares in the company. In this case, HL has a share price of £7.70 and normalised earnings of 66p, giving it a normalised earnings yield of 8.6%. The dividend yield is 5.2%, so that’s a 5.2% cash income for me, plus another 3.4% reinvested to fuel capital growth and dividend growth.

In each case, the cash yield (the dividend yield) is higher than the 4.5% on offer from a high interest fixed term savings account, but the total yield (the normalised earnings yield) is often as much as two or three times higher than you'll get from a savings account, and sometimes more than that.

Pro #2: Your income and capital are somewhat protected from inflation

Unfortunately, interest rates have been lower than the rate of inflation since 2008, 15 long years ago. As a direct result, savers have had their capital and income eroded by relentless waves of inflation ever since the Bank of England began its reckless experiment with near-zero interest rates.

Those days are finally over, and interest rates are back up to a more reasonable 4% or so, but with inflation still above 10%, hard-earned savings are being eroded faster than ever, which is a serious problem.

The good news is that one of the key benefits of dividends is that they can grow, even if you withdraw the dividend and spend every penny of it. That’s because (as we've seen) some of the income (i.e. the company’s profits) are reinvested back into the business to fund growth, and that is what allows dividend stocks to increase both their capital value and dividends in line with and perhaps even ahead of inflation.

Of course, when inflation is at 10%, very few companies are going to be able to keep up with that, but if inflation is closer to a more normal 2% or so, then most high-quality dividend stocks can easily outgrow that.

I'll use the previous three companies as examples again.

By reinvesting some of its earnings, MoneySuperMarket has grown its dividend by an average of 5% per year over the last decade.

Close Brothers managed a dividend growth rate of 2% (somewhat lower due to the effects of the pandemic).

And Hargreaves Lansdown upped its dividend by 9% on average over the last ten years.

Investors who were living off those dividends would have seen their income grow ahead of inflation while also benefitting from higher cash yields than a fixed-income savings account.

Pro #3 and Con #1: You have instant access to your capital

When you own shares, you can sell them pretty much any time you like, but this is both a con as well as a pro.

Having this liquidity is good because if a real emergency comes up and your emergency cash buffer (several months' worth of normal expenses held in an instant access savings account) isn’t enough, you can sell shares to plug the gap if you really have to.

But instant access is also a con because we might be tempted into becoming one of those infamous pensioners in Lamborghinis. I guess that is a risk, but as an adult, it’s a risk I'm willing to bear.

Con #2: Your capital is at risk

Perhaps the most obvious difference between savings accounts and dividend stocks, or between saving and investing more generally, is that investing involves the risk of loss.

Of course, it isn’t quite that straightforward because, as savers have found out over the last 15 years, just because the numerical value of the cash in your savings account doesn’t go down, it doesn’t mean the purchasing power (i.e. the economic value) of that money hasn’t been diminished by inflation.

But, ignoring inflation, at least with savings, you know that you can get your money back, which certainly isn’t true with investments.

With investments, there are two ways you can lose money. The first is when the intrinsic value of the investment goes down, and the second is when the market value of the investment goes down.

For example, imagine you decide to become a buy-to-let investor, so you buy a house for £1 million (it’s in London, so it’s a fairly ordinary three-bed semi). Here are two scenarios:

Scenario 1: The day after you bought it, a meteor hits the house and seriously damages it. No tenant wants to live in a half-demolished house, so you end your career as a landlord and sell to a local builder for £0.5 million, crystalising a £500,000 loss.

In this case, the intrinsic value of the house has declined because its ability to generate cash (rent) has declined, at least until someone rebuilds it.

Scenario 2: In an alternate universe, the meteor misses the Earth, so your house is fine. Instead, there was a house price crash because the Bank of England suddenly raised interest rates to 7%. Your friend Bob, who is also a landlord, offers you £0.5 million for your house. You’re worried about prices falling further, so you sell to Bob, crystalising a £500,000 loss.

In this second case, the intrinsic value of the house is fine because its ability to generate rent hasn’t changed (ignoring the impact of 7% interest rates on the economy and renters). However, the market value of the house has fallen because higher interest rates mean that homebuyers can only afford smaller mortgages.

All of this applies to dividend stocks in exactly the same way.

If you invest in a company and its ability to generate long-term earnings and dividends goes down, then the intrinsic value of the company has also gone down.

If you invest in a company and its share price goes down, then its market value has gone down.

As a general rule, selling just because the market value has fallen is a very bad idea. After all, it would be madness to sell a house just because your neighbour thinks it’s worth 20% less than it was last year, and likewise, it would be madness to sell a company's shares just because the share price (which reflects what other people think the company is worth) has gone down by 20%.

However, if the intrinsic value of a house or a company falls by a significant amount, then yes, it can make sense to cut your losses and sell up.

To avoid the risk that comes with falling intrinsic values, most dividend investors will try to invest in high-quality companies that are able to consistently grow their intrinsic value over the long term by reinvesting some of their steady earnings into new, productive assets.

Also, given that intrinsic values and market values can go down as well as up, it makes sense to invest in a diverse basket of quality dividend stocks, which is an extensive topic I’ll cover in a separate post.

Con #3: Your income could go down

Following on from the above point, companies are like buy-to-let houses, at least to some extent, in that you never really know exactly how much they’re going to earn in a given year.

Even so, a quality house and a quality company should both be able to earn a reasonably predictable income most of the time, and that’s why I use a normalised earnings yield rather than the current earnings yield (which can be materially affected if the latest profits were unusually high or low).

So, like a rented house, a company’s earnings aren’t guaranteed, and that means the dividend isn’t guaranteed either. Most high-quality dividend stocks will pay a fairly conservative dividend, perhaps covered twice over by earnings, so that even if earnings do go down in a given year, the dividend should be unaffected.

This allows the best companies to pay a progressively increasing dividend, bumping it up in line with or slightly ahead of inflation almost every year.

Weak companies, on the other hand, occasionally make losses, even during mild downturns, making their dividends very unreliable. This is why income investors should, as a general rule, stick to investing in companies that are both high-quality and relatively defensive, which means they're relatively unaffected by the ups and downs of the economy.

Again, diversification can help reduce this risk, so if a company does temporarily cut or suspend its dividend, the overall impact on your income should be relatively minor.

Conclusion: Savings vs. dividends, who wins?

As I said at the outset, it really depends on your desire for returns and your ability to handle uncertainty and risk. If you’re super-cautious and you don’t like the idea of putting your capital at risk, then savings accounts may be the way to go (although, of course, money in savings accounts is almost guaranteed to lose purchasing power, thanks to inflation).

If you can handle some volatility in your income and even your capital, then dividend stocks could be a good choice.

And, of course, you could always use both.

In my case, I have about 10% of my retirement funds in fixed-term savings accounts, partly as an experiment to see how the HL Active Savings platform works but also because savings rates are at least reasonably attractive now. I'm still in the accumulation phase, so the other 90% or so is in a diversified portfolio of 23 UK dividend stocks, where all dividends are reinvested.

There isn't anything magical about a 90/10 dividends/savings split, and there is no reason why the split between savings and dividends couldn’t be 50/50 or anything else.

Ultimately, adjusting the split between savings and dividend stocks (or bonds or anything else) is something we should all do because our retirement portfolios should be allocated in line with our personal preferences.

In the next post in this series, we'll look at how to find quality companies with consistent profits and dividends.

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.