This is a detailed review of PayPoint, a dominant market leader with a history of impressive growth.

Here's how PayPoint describes itself:

"PayPoint is the UK’s leading retail and payments services provider. Through our network of over 28,000 stores and with a 43% share of the UK convenience market, we make life easier for everyone through pioneering retail technology, services and omni-channel payments solutions serving millions of customers every day"

In plain English, PayPoint makes payment terminals where people can pay their utility bills at a local convenience store, either in cash or by card.

It does provide other products and services, but its core business is in-store bill payments.

Unfortunately for PayPoint, that core business is in decline because more and more people pay their bills online, or by direct debit or standing order. There's a big question mark over whether PayPoint can survive in a world of online and automated payments, and that's what makes PayPoint an interesting company to review.

Table of Contents

- Is PayPoint a quality company?

- Q1: Does PayPoint have a focused core business?

- Q2: Has PayPoint had the same core business for over a decade?

- Q3: Has PayPoint grown organically rather than through acquisition?

- Q4: Has PayPoint produced consistent and sustainable growth?

- Q5: Has PayPoint's profitability been consistently high?

- Q6: Does PayPoint benefit from network effects?

- Q7: Does PayPoint benefit from hard to replicate assets that make its products or services better, cheaper or more convenient?

- Q8: Does PayPoint benefit from core market leadership?

- Q9: Does PayPoint benefit from switching costs?

- Is PayPoint a defensive company?

- D1: Is PayPoint's core market largely unaffected by the economic cycle?

- D2: Is PayPoint largely unaffected by commodity prices?

- D3: Is PayPoint's core market expected to grow over the next decade or more?

- D4: Is PayPoint's core market unlikely to be disrupted within the next decade?

- D5: Is PayPoint free from significant concentration risk?

- D6: Is PayPoint free from significant product or patent risk?

- D7: Does it have prudent levels of debt?

- Is PayPoint good value?

- Conclusion

- PayPoint and the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

Is PayPoint a quality company?

Q1: Does PayPoint have a focused core business?

YES - PayPoint provides payment processing services to large consumer services organisations, such as utility companies, mobile telecoms companies, housing associations and the government.

These payment services include payments made online, but the key feature of PayPoint’s service is that it can accept offline payments through a network of almost 30,000 retail partners, most of which are convenience stores. This makes PayPoint very attractive to large organisations that need to give their customers the option of paying offline.

For example, in the UK you almost have to have a TV Licence, so it would be unfair for the government to force people to pay online or even by card. To enable people to pay by card or cash offline, the government partners with PayPoint so that people can pay for their TV licence at a local store.

This is good for PayPoint's clients (those large consumer services organisations), but what about the retailers who have to install a PayPoint terminal and spend time processing those bill payments. What's in it for them?

The answer is that PayPoint offers retailers a range of services to drive people into their stores where those people will hopefully buy something. These services include:

-

PayPoint Terminal: This sits next to the retailer's till and allows the retailer to accept mobile phone top-ups, gas bill payments and other payments to PayPoint's clients.

-

Card Terminal: This enables the retailer to take card payments for general items in their store. Lots of companies provide these terminals but it can be convenient for the retailer to have this from PayPoint as well as the terminal.

-

PayPoint One (EPoS, electronic point of sale system): This takes the PayPoint Terminal and Card Terminals a step further and integrates both into a tablet-based electronic till with optional inventory management software that connects directly to wholesalers. This helps PayPoint embed itself deeper within each retailer's business.

-

ATMs (by LINK): Rather than taking cash to the bank (which incurs a fee), retailers can take cash from the till and put it into the ATM. Customers then get cash from the ATM and give it back to the retailer when they buy something.

-

Collect+: This is the UK’s leading PUDO (parcel pick-up/drop-off) service and is another way to drive people into the store.

The online side of PayPoint's payment services is called MultiPay. This usefully broadens PayPoint's payment processing capabilities beyond convenience stores and into the online world, but it's really an add-on to the core offer which is offline payment processing for large consumer services organisations.

Q2: Has it had the same core business for over a decade?

YES - PayPoint’s core business of providing store-based payment processing services has remained broadly the same since it was founded in the mid-90s.

The focus was initially on cash payments for utility bills, but this has since broadened to include a wider range of clients (such as housing associations or mobile telecom companies) and a wider range of payment types (notably online and mobile payments).

The services offered to retailers have also broadened to include an electronic till, inventory management software and a parcel pick-up/drop-off service, but the basic model has remained the same.

Q2: Has PayPoint had broadly the same goal and strategy over the last decade?

YES and NO - PayPoint’s goal was always to be the leading provider of payment services to utility companies and large consumer services organisations, centred around its ability to accept payments at local stores.

Its core strategy has also remained more or less the same and is based on the two-sided market model used by companies such as Facebook, eBay and Amazon. It works like this:

- Retailers will only want a terminal in their store if it's going to attract lots of customers, so that means partnering with the terminal provider who accepts payments for the largest number of utilities and consumer services organisations.

- PayPoint's founders realised this, so they worked together with a range of utility companies so that PayPoint had the widest range of clients from day one.

- This allowed PayPoint to install more terminals than the competition because its terminals were more attractive to retailers.

- Once PayPoint had the largest network of retailer partners, it was then attractive to other utility companies because their customers would be able to pay at the widest range of local stores.

- This allowed PayPoint to attract yet more utility companies, which then attracts more retailers, and so on until PayPoint is the dominant market leader with a 40% market share.

This positive feedback loop between clients and retailers is known as a network effect. It’s an incredibly powerful competitive advantage and, quite sensibly, PayPoint has stuck to this basic model from day one.

However, I've answered both yes and no to this question because PayPoint hasn't always had the same strategy. In fact, there was a significant strategic shift in 2015.

Here’s the backstory:

In the late 2000s, PayPoint began to expand into additional payment channels and into other countries. Management knew that at some point it would run out of places to install its terminals and they wanted to continue the company's early history of rapid growth.

The first move beyond its core in-store bill payments business was to acquire a couple of internet payments businesses in 2007. The idea was that PayPoint would provide its large clients with all their payment needs, both online and offline.

This is known as expanding your share of the customer’s wallet and it's a very common and sensible strategy.

However, one of the acquired businesses came with 3,500 customers who were only using online payments. At first glance, this seems like a nice extension of the PayPoint business model into the high-growth area of Internet payments.

But there was a problem. Ideally, when a company expands into a new market, I want to see that expansion do one or both of two things:

-

Leverage the company’s existing competitive advantages to make success in the new market highly likely;

-

Have some sort of positive impact on the company’s competitiveness in its existing markets.

The problem was that providing only internet payment services to 3,500 online businesses had nothing to do with PayPoint’s core business of accepting in-store bill payments.

Offering standalone internet payments to, say, an online clothing business wouldn’t benefit from PayPoint’s dominance in offline bill payments, and it wouldn’t strengthen the core business either.

With no connection to the existing core business, this was unlikely to be a successful acquisition.

A few years later, PayPoint expanded overseas by acquiring a company providing pay-by-phone services to car parks in the UK, Canada, the US and France.

I have no idea what taking payments for a car park in San Francisco has to do with PayPoint’s core business of offline bill payments in convenience stores. Yes, both are high-volume payment processing businesses, but that's a tenuous and irrelevant connection.

So (to get back to my point) what was the strategic shift that occurred in 2015?

The shift was to refocus on the core UK offline payments business by selling the pay-by-phone and online payments business, which had done little more than distract management for several years (although to be fair, it seems that much of the technology from these businesses was used to build what is now PayPoint’s online MultiPay service).

This was a fairly major strategic shift because management had long had its eye on expansion into new markets. By admitting defeat with these acquisitions, management was effectively saying that moving beyond PayPoint’s core offline payments business was going to be incredibly hard.

What this story tells me is that (a) PayPoint has no deeply ingrained culture of disciplined expansion into new markets and (b) its core business is strong enough to survive the occasional strategic error.

Q3: Has PayPoint grown organically rather than through acquisition?

YES - Companies that grow organically have shown that they can compete and win consistently over a long time, whereas any idiot can acquire lots of companies by taking on massive amounts of debt.

Thankfully, almost all of PayPoint's growth has been organic. However, the company has made several large acquisitions along the way, so they're worth looking at:

2006: Metacharge (£8m)

Metacharge processed payments online, by telephone and by email. It had 500 existing clients and was a large acquisition for PayPoint back in 2006 (by large, I mean it cost more than PayPoint's average earnings at the time).

The basic premise for this acquisition was to add internet and other payment channels to PayPoint's offer, so it could fulfil a wider range of payment needs for its large consumer services clients. That's very sensible and some of Metacharge's technology likely still exists inside PayPoint's MultiPay system.

What wasn't so sensible, in my opinion, was taking on Metacharge's existing 500 clients that didn't need access to offline cash payment services. Those clients had nothing to do with PayPoint's core business and eventually, they became a loss-making distraction for management that was sold off in 2016.

2007: SECPay (£12m)

This was a pure internet payments business with 3,500 clients and was another relatively large acquisition at the time.

As with Metacharge, this acquisition made sense from a technology point of view, adding further internet payment capabilities to broaden out PayPoint's offer to its large consumer services clients.

However, management also thought PayPoint could expand into pureplay internet payment services, even though this doesn't benefit or leverage PayPoint's core offline payments capabilities.

This also became a loss-making distraction that was sold in 2016.

2007: Pay Store SRL (£15m)

This was a Romanian mobile phone top-up company with terminals in local convenience stores. It was another relatively large acquisition, but at least this time the rationale was near perfect. I'll let the CEO explain why:

"This acquisition is in accordance with our strategy to replicate our UK model in other markets and provides [...] us with a foothold in the rapidly expanding Romanian market. We intend to extend the existing distribution channels to take advantage of the migration of mobile airtime from scratch cards to electronic top-ups. In addition, we intend to roll out a branded bill payment service for the 97% of householders who pay in cash, providing convenient retail outlets close to where they live or work."

In other words, PayPoint bought a carbon copy of itself which was still rapidly rolling out terminals, where PayPoint could leverage its existing core expertise in offline payments for consumer services.

In 2017, PayPoint acquired Payzone Romania for £2m and bolted it onto the existing Romanian business, and in 2020 the entire Romanian operation was sold for £47m, netting the company a very healthy capital gain.

This is a good example of what can happen when a company expands into a new market that is very closely associated with its core business, where it can extend existing competitive advantages into that new market.

2010: Verrus (£33m)

Verrus was an international car park payments processor, taking payments via its pay-by-phone app. This acquisition was similar to PayPoint's other failed technology-based acquisitions because:

-

It was large, costing more than twice PayPoint's ten-year average earnings

-

It was technology-based (PayPoint wanted to acquire pay-by-phone capabilities) and

-

It had existing clients which had nothing to do with PayPoint's core offline payments business

On the plus side, bolting a pay-by-phone app onto PayPoint's existing omnichannel offering would be attractive to large consumer services organisations, enabling them to take payments online, offline, via mobile app, text, card and so on.

But the rest of Verrus's business was based around mobile payments for car parks in France, Canada and the US. Exactly what that has to do with accepting offline payments for gas bills in the UK is beyond me.

Clearly, the answer is nothing, as this business also became a loss-making distraction that was sold in 2016.

The CEO summed up these lessons in the 2015 annual report:

"The mobile and online [payments] market has attracted a substantial amount of new investment, particularly last year. This investment has changed the competitive landscape, bringing pressure for both faster development and larger scale to support lower margins. The need for greater pace and scale has increased the execution risk and extended the timetable for returns for PayPoint. Positioned against the opportunities centred around our retail proposition, the board believes that there are likely better owners for these businesses and as a consequence has decided to sell the parking and online payment processing companies"

A summary of that statement would be:

-

Attractive high-growth markets attract lots of competition

-

PayPoint's online and mobile businesses had no meaningful competitive advantages in those markets

-

PayPoint's core business has huge competitive advantages and is, therefore, a much better place to invest shareholder capital

Avoiding markets where you cannot win is an important lesson, but PayPoint's most recent acquisitions are a sign that it has already forgotten this lesson.

2021: Handepay and Merchant Rentals (£70m)

These two companies are effectively one, with Handepay providing small and medium businesses (SMEs) with card/phone payment terminals and Merchant Rentals providing financing for those terminals.

This is another large acquisition at just over twice PayPoint's ten-year average earnings and in many ways, it looks eerily similar to PayPoint's earlier and unsuccessful acquisitions.

Like those acquisitions, this one has lots of customers (30,000 small UK businesses) operating outside PayPoint's core convenience store network. These are restaurants, garages, hairdressers and other businesses where management hopes PayPoint can expand and (somehow) realise synergies with the existing core business.

However, I see no obvious connection between PayPoint's core business of accepting offline utility bill payments and the acquired businesses which offer card payment terminals to garages and other small businesses. In other words, I don't think people are going to pay their gas bills or top up their mobile phones at their local garage.

Also, there are no obvious network effects in the card terminal market and there are lots of companies offering lots of essentially identical terminals. I may be missing something, but from where I’m sitting, I can’t see any reason why PayPoint is better placed to compete in this market than any of the existing card terminal providers.

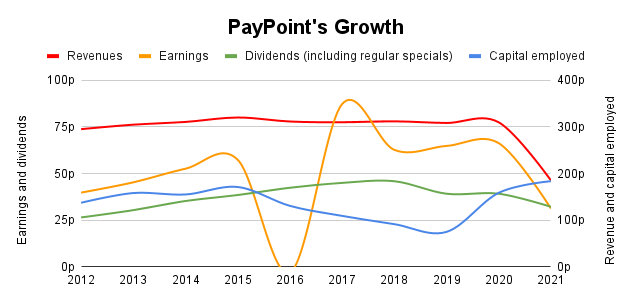

Q4: Has PayPoint produced consistent and sustainable growth?

NO - During its first two decades, PayPoint was a young and fast-growing business.

It was founded in 1995 after a moment of inspiration from co-founder Rob Farbrother. The first few years were spent getting the business off the ground, helped by a group of utility companies that funded the early research and development costs.

Things really started to get serious in 2002 when PayPoint made its first profit. Once the company was able to fund growth by reinvesting profits, it really took off.

From 2002 to 2009, PayPoint increased its revenues from £26m to £224m, EPS went from 1p to 35p and the dividend went from zero to 18p.

It did this by rolling out thousands of terminals to convenience stores across the UK. For example, in 2002 it had a network of 8,000 terminals. By 2005 that had increased to 13,000 and by 2009 there were 22,000.

It was a great success story, but this "rollout phase" doesn’t last forever. There are only so many convenience stores in the UK and at some point, PayPoint would run out of places to install new terminals.

This shows up as a dramatically slowing growth rate for PayPoint's terminals in recent years, with the total going from 28,000 in 2015 to barely 29,000 six years later.

The saturation of its terminals in the UK, along with the sale of those failed acquisitions, has left PayPoint with zero revenue growth over the last decade.

To be fair, there has been some continued growth in earnings, especially earnings per store, driven by new services such as MultiPay PayPoint One and Collect+. But without revenue growth, earnings growth is going to be very limited.

However, management does have plans to get growth going again and I'll cover those plans in a later question.

Also, given the lack of growth, PayPoint has easily funded itself over the last decade with retained earnings rather than having to take on lots of debt or lease obligations. In other words, its recent (almost non-existent) growth rate is easily sustainable.

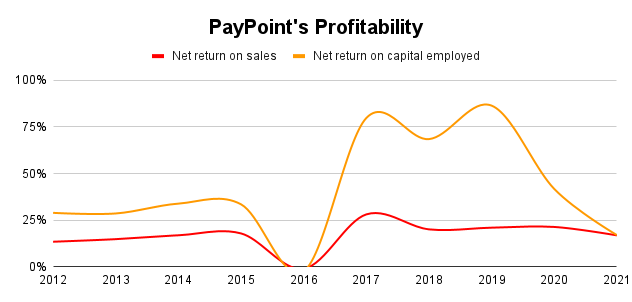

Q5: Has PayPoint's profitability been consistently high?

YES - PayPoint has produced exceptional net returns on capital, averaging more than 30% over the last decade. Profit margins are also good at more than 15%.

In the chart above you can see that PayPoint’s return on capital jumped up after 2016. That was due to a £49m write-down of the value of some acquired businesses.

This write-down caused a loss for the year and, interestingly, management barely mentioned the loss or the write-down in the 2016 annual results. In my opinion, management should be frank with shareholders about problems, so this is not a good sign.

Anyway, the write-down reduced the value of PayPoint’s capital employed. However, earnings stayed about the same because the businesses that were written down were loss-making, so the overall return on capital increased.

Q6: Does PayPoint benefit from network effects?

YES - As I've already mentioned, PayPoint’s core strength is the network effects that are central to its business model:

- It has the largest network of retailers accepting offline payments for consumer services, from gas and electricity bills, mobile phone top-ups, travel card top-ups, the TV License and much more.

- This makes PayPoint the de facto standard choice for large consumer services organisations looking for a way to accept offline payments.

- PayPoint also has the largest network of consumer services organisations as clients, so it accepts payments for the widest range of utility and consumer services.

- This makes it very attractive to convenience store retailers because a PayPoint sign in the window is sure to attract a wide range of potential customers to the store.

This is a classic network effect business, with a positive feedback loop between the size of the client and retailer networks. This is virtually impossible for competitors to break and it explains PayPoint's more than 40% market share.

Having said that, one competitor is a constant thorn in PayPoint's side, and that's the Post Office.

The Post Office is a strange beast. It's a profit-seeking company, but it's also a regulated monopoly that is ultimately owned by the UK government. That makes it almost impervious to normal competitive pressures.

PayPoint and the Post Office have been rivals almost from the beginning, with PayPoint repeatedly pushing to have the Post Office's monopoly powers rolled back in the name of greater competition, better services, lower prices for consumers and of course, more profit for PayPoint.

This particular thorn has become even more problematic because in 2018 the Post Office acquired Payzone, PayPoint's main competitor. The acquisition combined the 13,000-terminal Payzone network with the 11,500-branch Post Office network, creating an over-the-counter payment processing network to rival PayPoint’s.

PayPoint probably feels like the UK TV channels that have to compete against the BBC.

Still, PayPoint's network effects are extremely powerful and I don't expect its core business to fail through a lack of competitiveness.

Q7: Does PayPoint benefit from hard-to-replicate assets that make its products or services better, cheaper or more convenient?

NO - The only hard-to-replicate assets that PayPoint has access to are its networks of clients and retailers, and we've already looked at those.

The PayPoint name is well-known, but if PayPoint didn't have the biggest networks I don't think clients or retailers or consumers would care if they used PayPoint or Payzone.

A company's culture can also be a valuable and hard-to-replicate asset. But PayPoint doesn't seem to have a “great culture”, at least according to the Good to Great concepts developed by Jim Collins:

-

There isn’t an obvious obsession with getting the right people on the bus.

-

There doesn’t seem to be a great appreciation for what PayPoint does better than anyone else because it has repeatedly tried to expand into markets where it isn’t better than anyone else.

-

It doesn’t use the bullets then cannonballs approach to expansion. Instead, it makes fairly large acquisitions that usually haven’t worked out.

Overall then, PayPoint seems like a so-so company that has been able to dominate due to a combination of network effects and first-mover advantage.

Q8: Does PayPoint benefit from core market leadership?

YES - This goes hand in hand with network effects. To really benefit from network effects you have to be the market leader. If you're not the market leader then the market leader will have stronger network effects (assuming the business model has network effects) and will likely crush you, or at least make it incredibly hard for you to beat them.

PayPoint is the market leader, it has network effects and I would really not want to compete against it (unless I happen to be a regulated monopoly like the Post Office).

Q9: Does PayPoint benefit from switching costs?

YES - There are switching costs for PayPoint's retail partners and its consumer services clients.

For example, if a retailer wants to switch to another card terminal provider, that isn't the end of the world. But if it wants to replace PayPoint's electronic till, inventory management system, parcel pickup and drop off service and ATMs, that's a lot of work.

The same goes for PayPoint's consumer services clients. If a company is using MultiPay for online payments and PayPoint's retailer network for offline payments, those are relatively deep integrations. It's going to take time, effort and money to switch to another payment processor.

However, it can be done, and in recent years British Gas has switched completely from PayPoint to Payzone and Utilita switched its online payments to an in-house system. Even so, there are material barriers to exit.

Is PayPoint a defensive company?

D1: Is PayPoint's core market largely unaffected by the economic cycle?

YES - PayPoint generates most of its revenues and profits when people pay their rent, gas and other bills in-store or online, and these transactions need to be paid regularly, whether there's a recession or not.

This defensiveness showed up in the 2008 to 2012 period, when the UK almost saw a double-dip recession, yet PayPoint's business was left virtually untouched.

D2: Is PayPoint largely unaffected by commodity prices?

YES - Commodity prices impact people's gas and electricity bills, but PayPoint's revenues and generated from a diverse array of sources, so commodity prices are not particularly relevant.

D3: Is PayPoint's core market expected to grow over the next decade or more?

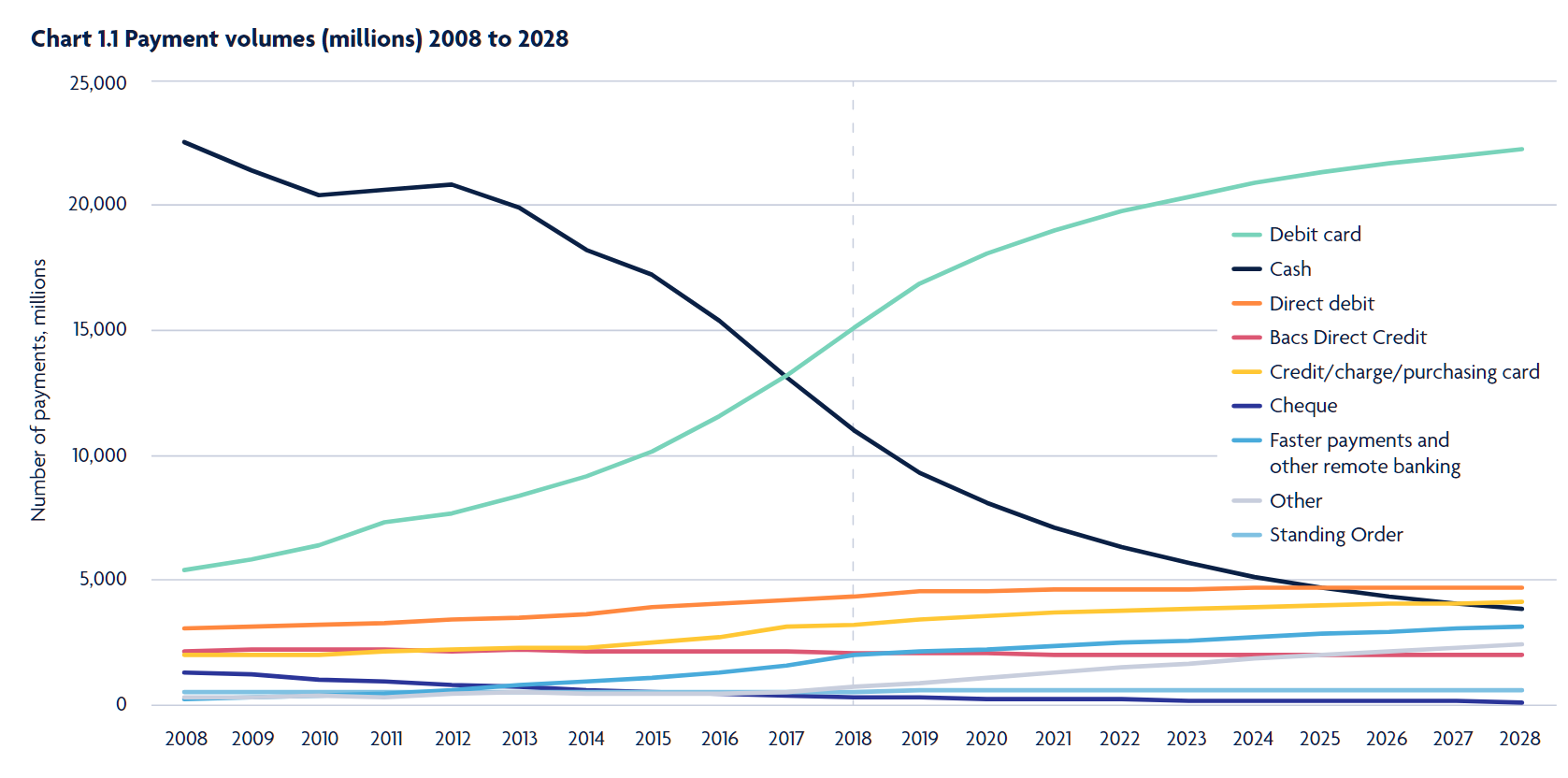

NO - PayPoint's core business enables people to pay their bills offline at a convenient location.

In the good old day, someone might walk into their local convenience store and pay for their electricity or TV licence using a fistful of fivers. But the use of cash for that sort of transaction has been declining in the UK for many years, and the pandemic has massively accelerated the transition towards online payments.

In short, PayPoint’s core market is declining at a fairly rapid pace.

Source: UK Payments Market Summary 2019 (PDF)

As more people pay their bills by debit card, fewer need to go into a store to pay because it’s easy to set up recurring payments.

Of course, some people will always want to pay in cash or in-store, but they’re a shrinking minority.

The real question is where will cash payments be in 2030 and beyond?

Surely by then almost everyone will have a computer (whether it’s a desktop, tablet or smartphone) and will be able to transfer money in and out of their bank account or “digital wallet”. They’ll be able to pay their utility bills and other consumer services online and on their mobile phone, and only a tiny minority will want to pay for those things in a convenience store.

Of course, PayPoint accepts online payments via its MultiPay service, but that service depends upon the competitive advantage generated by its retailer network.

If almost nobody pays their bills in-store, then few service companies will care about accepting offline payments. And if they don’t care about offline payments, they can get their online payment services from any one of a dozen major providers, or even build their own system with relative ease.

Fortunately, PayPoint does provide other services which don’t depend on people paying bills in-store. It provides retailers with an EPoS system, it has inventory management software, card payment terminals and the UK’s leading parcel pickup/drop-off service. Unfortunately, these either have no competitive advantage or they’re so small as to barely make any difference.

For example, what makes PayPoint’s EPoS different to any other modern EPoS? The answer is, not a lot. The same goes for its card terminals and the Collect+ business is currently sub-scale and doesn’t make much or perhaps any profit. As far as I can tell, without the core offline bill payments business, PayPoint has nothing special to offer.

This is why the company spent £70m acquiring card payment terminal businesses in 2020. It’s desperately looking for ways to move away from cash, but I don’t think acquiring businesses in markets where PayPoint has no obvious competitive advantage is the way to do it.

D4: Is PayPoint's core market unlikely to be disrupted within the next decade?

NO - Technological disruption goes hand in hand with the decline of cash. Over many decades we’ve seen the introduction of credit cards, debit cards, standing orders, direct debits, PayPal and now Apple and Google Pay. All of these undermine the use of cash for anything but the smallest of transactions for most people.

Short of nuclear war, I see nothing to stop the continuing decline of cash and in-store bill payments over the coming decade, as tech-savvy millennials and Gen-Z become the majority of bill payers.

This will inevitably undermine PayPoint’s core in-store bill payments service, and as that becomes less important, its competitive advantages (those network effects) are likely to become far less powerful.

D5: Is PayPoint free from significant concentration risk?

YES - PayPoint does have large contracts with large consumer services organisations. A good example would be its contract with British Gas, which was lost in 2020 when British Gas moved over to the Payzone/Post Office network.

However, even a very large utility such as British Gas only generated around £5m of PayPoint’s revenues. That's below my definition of a dangerously large customer, which is one that generates more than 10% of overall revenues.

D6: Is PayPoint free from significant product or patent risk?

YES - Although PayPoint’s hardware and software need to be updated every few years, I don’t see this as a material risk. As long as the functionality is in line with competitors then PayPoint’s network effect should still attract clients and retailers.

D7: Does PayPoint have prudent levels of debt?

YES - PayPoint’s debts are relatively low as it doesn’t need to invest in heavy capital equipment to grow. It has debts of around £90m, which is about 2.5 times its average earnings. I would be comfortable with anything up to four times earnings.

Defensiveness summary: PayPoint's core in-store bill payments market is defensive, but it's also declining and any company with a declining core market cannot really be defensive.

Is PayPoint good value?

V.1: Is PayPoint free from serious near-term problems?

NO - PayPoint's core business of in-store bill payments is in decline and the pace of decline makes it a relatively near-term problem.

This isn't something that is going to take decades to play out, such as the decline of cigarette smoking. In my opinion, by the end of this decade, in-store bill payments are likely to be a very marginal activity, so PayPoint's core business may be largely obsolete within a decade.

This doesn't mean the company is inevitably going to go bust, but it does mean it has to build a new core business, and that's going to be very difficult (but not impossible) to achieve.

V2: Is PayPoint's dividend likely to grow over the next decade and beyond?

YES and NO - I’ll start with the positive. I think it’s realistic to say that PayPoint is likely to increase its dividend over the next ten years.

That’s because the dividend had already been cut before the pandemic, taking it from a high of 46p to 32p. I think the current dividend is at a conservative and sustainable level with room to grow over the next few years.

However, looking longer-term, I think the decline of its core in-store bill payments business is very likely to limit its ability to grow the dividend beyond the end of this decade. It may even go into permanent decline.

Of course, I don't have a crystal ball and its recent acquisitions operating in the broader card terminal market could drive the company's growth for decades to come. But I don't think those businesses have any durable competitive advantages, so I have no confidence that they'll thrive and prosper over the long term.

V3: What is a realistic and conservative estimate of PayPoint's future dividends?

To estimate PayPoint's fair value we need to build a dividend model. That's because the present value of a company depends upon the cash it will pay to shareholders in the future.

The estimate should be both realistic and conservative, so here are the assumptions I’ve used to build my dividend model:

-

Going forwards, the return on capital averages 25% which is conservative relative to PayPoint’s historical average.

-

Dividend cover stays within management's target of 1.2 to 1.5.

-

Dividends and earnings grow by almost 6% per year over the next decade, partly due to the post-pandemic recovery. Record earnings and dividends are produced by 2030.

-

Long-term growth is zero as there is much uncertainty around PayPoint’s ability to successfully pivot away from in-store bill payments. Zero growth means PayPoint slowly shrinks as it fails to keep up with inflation.

According to this model, fair value (i.e. the price at which the shares would produce returns in line with the market average) is £6.98. I call this the "sell price" because I don't want to own shares where expected returns are no better than an index tracker.

Also, the "buy price" in the table above is my target purchase price (although even lower would be better) and the "margin of safety" is what it sounds like.

V.4. Is there a sufficient margin of safety between PayPoint's share price and fair value?

NO - The idea of a margin of safety isn't new and it isn't confined to the world of investing. Anything that involves a degree of uncertainty or risk requires a margin of safety.

In my case, I calculate a margin of safety score which just tells me where the current price is in relation to (a) fair value (my "sell price") and (b) my target purchase price (the "buy price" in the table above).

At the time of writing, PayPoint's shares were just over £7.00 each. That's slightly above my sell price of £6.98. Since PayPoint's price is above my estimate of its fair value, it has a negative margin of safety of minus 5%.

Because the current price is above my estimate of fair value, I assume that PayPoint will produce long-term returns that are below average (although of course, I can't know this for sure).

Conclusion

Overall, I think PayPoint is a quality business with durable competitive advantages, but its core business is in decline and that's a major problem for a long-term investor like me.

I don't think the current price is attractive, but even if the price fell to £4.50 (below my target buy price) I still probably wouldn't invest. That's because I don't like to invest in turnarounds or transformations, and that's what PayPoint is.

Remember, you always have to compare any potential new investment against what you already own. If it isn't better than most of your existing holdings then you're probably better off investing your spare cash or dividends into your best existing holdings (assuming, of course, that you're already reasonably well-diversified).

PayPoint and the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

PayPoint has been a holding in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio since 2017. I bought it at a time when I was less wary of turnarounds and transformations, and the returns have been positive but unspectacular.

After carrying out this review, I removed PayPoint from the portfolio and added it to my blacklist, which is a list of companies where the combination of quality and defensiveness do not meet my standards.

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.