Burberry is one of the world's leading luxury fashion brands and a popular holding among "quality growth" investors.

Burberry also has a long and consistent track record of dividend growth, so it's popular with dividend growth investors too.

In this post, I'm going to review Burberry and its share price in some detail, from the perspective of a dividend growth investor.

I'll walk you step-by-step through Burberry's most important features, using the investment checklist I've developed over more than a decade.

Table of Contents

- Is this company high quality?

- Q.1. Does it have a focused core business?

- Q.2. Has it had the same core business for over a decade?

- Q.3. Has it had broadly the same goal and strategy for over a decade?

- Q.4. Has it earned consistently good returns?

- Q.5. Has it produced consistent and sustainable growth?

- Q.6. Has the company avoided large transformation projects?

- Q.7. Has management avoided excessively rapid expansion?

- Q.8. Has most of its growth been organic rather than through acquisitions?

- Q.9. Does the company benefit from network effects?

- Q.10. Does the company benefit from valuable and hard to replicate assets?

- Q.11. Does the company benefit from core market leadership?

- Q.12. Does the company benefit from switching costs?

- Is this company defensive?

- D.1. Is the company’s core market defensive?

- D.2. Is the core market expected to grow over the next few decades?

- D.3. Is the core market relatively free from regulatory risk?

- D.4. Is the core market unlikely to be disrupted?

- D.5. Is the company free from significant concentration risk?

- D.6. Is the company free from significant product or patent risk?

- D.7. Is the company largely unaffected by commodity prices?

- D.8. Does the company have prudent financial leverage?

- Is this company good value?

- Final Decision: Are you happy to own this company at this price?

Is this company high quality?

Q.1. Does it have a focused core business?

YES - Burberry’s core business is designing, manufacturing and selling luxurious and fashionable clothing and accessories. The best example is its well-known trench coats, but Burberry’s range extends into the usual suspects of coats, handbags, shoes, trousers, t-shirts and so on.

These items are sold to a niche market of people who are willing to pay lots of money for Burberry’s products either because (a) they love Burberry’s combination of design, quality and heritage, (b) they want other people to know they can afford Burberry’s prices, or (c) a bit of both.

To use an analogy from an area I’m more familiar with, you could say that Burberry is to clothing as Rolls-Royce is to cars: an icon of British luxury.

Q.2. Has it had the same core business for over a decade?

YES - Burberry has existed since 1856, when Thomas Burberry first went into business as an outfitter.

Since then, the company has been through many twists and turns (including almost 50 years under the ownership of Great Universal Stores), but it has always been a clothing business selling relatively high-end clothing, although the emphasis has shifted over the years from practical to fashionable.

Q.3. Has it had broadly the same goal and strategy for over a decade?

YES - Beginning in the late 1970s, Burberry focused more and more on leveraging its well-regarded brand and heritage through licensing deals. The licensee would do all the design, manufacturing and selling, while Burberry would sit back and earn a fee by letting other companies use its house check, name and logo.

This gave Burberry an infinite return on capital because no capital investment was required. Unfortunately, it also seriously damaged the company's brand.

What makes the Burberry name valuable and hard to replicate is (a) its long history as an outfitter to famous adventurers and explorers, and as an official outfitter and weatherproofer to the royal family, (b) the brand's association with famous actors, models and other celebrities and (c) the fact that its most iconic products, notably the Heritage trench coat, have been hand made in Britain for more than a century.

When you allow the Burberry house check and brand to be used on anything from dog collars to baseball caps, it becomes ubiquitous and affordable and, therefore, unattractive to its core luxury customers.

The low point came in the late 1990s when Burberry, thanks in part to the success of the Burberry baseball cap, became associated with parts of society with which it would rather not be associated.

A turnaround was initiated, focused on restoring Burberry to its previous position as a luxury fashion brand.

The basic strategy was obvious: Regain control of the company’s designs and brand from license partners and drop all products that could damage the brand. This strategy was successful for several years and when Angela Ahrendts became CEO in 2006, she took it a step further.

Almost everything was brought in-house and all customer-facing design decisions (whether those decisions affected clothing, in-store decorations or the company's website) were centralised.

Instead of focusing on items that were low-priced and easy-to-sell, she wanted the company to re-focus on its iconic (and high-price) trench coat, combining innovative designs grounded in the company’s heritage with exceptionally high-quality materials and high-quality manufacturing in Britain.

This worked like a dream and, with various updates and tweaks, the same strategy stayed in place until 2017. From the low point in 1999 to 2017, Burberry’s revenues grew from £125 million to £2,766 million; a more than 20-fold gain in less than 20 years.

In 2018 a new CEO arrived, in part because revenues and earnings had more or less flatlined for several years. This new CEO introduced an updated version of the existing strategy, which remains in place today.

That strategy is to push Burberry even further up the luxury ladder, moving from its previous position in contemporary luxury up to the highest levels of pure luxury fashion.

The key features of the strategy are:

- Higher prices (to drive higher returns on capital)

- A fashion-forward mindset (think catwalk model rather than everyday wear) and

- Positioning the brand higher up the luxury ladder (by, for example, stopping sales through mid-market department stores and focusing instead on sales through Burberry’s website, its own high-end stores and high-end department stores and wholesalers).

This repositioning is being funded by targeted cost cuttings and efficiency gains, based on simplification, optimisation and automation.

This strategy is really a very mild evolution of what Burberry was already doing, so to answer the question at hand (whether Burberry has had the same goal and strategy for more than a decade), I would say yes, Burberry has had the same goal of being a leading global luxury fashion brand, pursued with the same strategy of moving gradually up the luxury fashion ladder, for well over a decade.

Q.4. Has it earned consistently good returns?

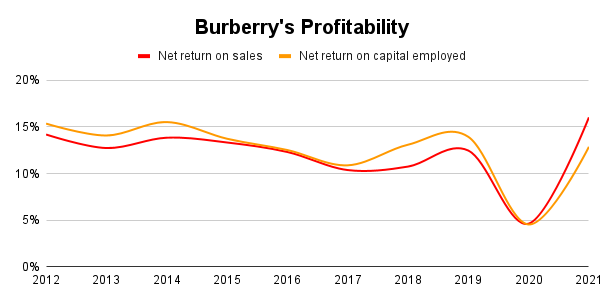

YES - If we ignore the pandemic then Burberry produced average net returns on capital over the last decade of almost 14%, which is well above average and above my 10% hurdle rate. Net return on capital was also above 10% in every one of those years, so it was consistently above average.

Burberry’s profit margins over the last decade (ignoring the pandemic) were also consistently good at more than 10% every year.

Interestingly, this chart highlights a gradual decline in profitability over the last decade. This may have something to do with why a new CEO was brought in during 2017/18.

Q.5. Has it produced consistent and sustainable growth?

YES - Burberry is a clothing retailer, so you have to expect some volatility in its returns as clothing is a notoriously cyclical industry.

However, other than a small loss in 2009 (mostly due to one-off costs resulting from the global financial crisis), Burberry has produced relatively consistent profits, dividends and growth for decades.

Revenue per share growth has averaged 5%, although the pandemic held this back over the last year or two.

Capital employed, which is the real engine room of growth for most companies (as it’s made up of factories, warehouses, retail stores, acquisitions and other valuable assets) has grown by almost 7% per year, on average, and hasn’t been materially impacted by the pandemic.

Burberry's growth has been funded primarily from retained earnings. In other words, it didn’t take on huge amounts of debt to buy raw materials, fit out stores, build warehouses and so on. And it didn’t take on lots of lengthy leases in an attempt to carpet bomb the world with Burberry stores.

You can see the three primary components of capital employed and how they’ve grown in the chart below.

Driving growth by reinvesting retained earnings is by far the most sustainable and lowest-risk way to grow a business, and it’s something that companies with consistently high returns on capital like Burberry are ideally suited for.

Also, just in case you were wondering, shareholder equity declined from 2017 to 2019 as the company returned excess cash to shareholders through a series of fairly large share buybacks, so this shrinking of shareholder equity isn't a sign of decline.

Q.6. Has the company avoided large transformation projects?

YES - I think it would be reasonable to say that Burberry went through something of a transformation from the late 1990s to the late 2000s when it moved from a business model of distributed design, brand licensing and low-cost accessories to a centralised, in-house model-focused around the trench coat.

But this shift occurred more than a decade ago and since then Burberry has not embarked on anything approaching a “transformation” project.

Q.7. Has management avoided excessively rapid expansion?

YES - There is no doubt that Burberry went through a period of very rapid growth between 1999 and 2015. As I’ve already mentioned, revenues went up more than 20-fold in less than 20 years and that requires a growth rate of more than 15% per year across those 20 years.

For a company producing net returns on capital of less than 15%, the only way to grow by 15% or more is to use outside funding from debt or leases. That’s risky, and to some extent, Burberry was going down that route as its borrowings increased from nothing before 2005 to £245m in 2009.

Fortunately, it seems the financial crisis of 2009 shocked management out of using this risky route to growth before the company’s debts really got out of hand. After 2009, debt started to come back down again, and that gave the company a nice strong balance sheet to deal with the pandemic.

I would say that Burberry’s growth from 1999 to 2015 was about as fast as a prudent person would want the company to grow. Every year it was opening lots of new stores, taking on lots of new staff and developing lots of new products. All this newness is an operational risk because all those people have to be trained up, they take time and attention away from actually running the business, they make more mistakes and so on.

Building a company is a lot like building a model aeroplane; the faster you build it the more likely it is to fall apart.

So Burberry just about managed to avoid major growing pains in the 2000s, and over the last decade, its growth rate has been considerably slower and more manageable.

Q.8. Has most of its growth been organic rather than through acquisitions?

YES - Burberry has never been particularly acquisitive and in the last decade, it made almost no acquisitions. Those it did make were very closely related to the core business and tended to be acquisitions of existing joint ventures or suppliers.

Q.9. Does the company benefit from network effects?

NO - Burberry’s products do not become better or more attractive just because more people buy them (in fact ubiquity has the opposite effect for luxury items), so it has no network effects.

Q.10. Does the company benefit from valuable and hard-to-replicate assets?

YES - Burberry’s most important, valuable and hard-to-replicate asset is its brand and all the history that comes with it.

I’m not a fashion person, so I’ll use Ferrari as an analogy. Some people buy Ferraris because of the way they look, the way they drive, the way they sound, and the incredible engineering and technology. But I would guess most people who buy a Ferrari choose it over other similarly competent supercars because it’s a Ferrari.

Ferrari has history. Tons of it. It’s had legendary battles at the Le Mans 24hr race and legendary drivers and wins in Formula 1. It’s designed some of the most beautiful cars ever to drive on public roads. Lots of people grow up dreaming of owning a Ferrari. The brand means something to those who care about such things and if you want to build a brand to compete with Ferrari, good luck with that.

Burberry, I imagine, is similar for people who are into luxury and fashion, especially British luxury and fashion.

Burberry has been around for more than 150 years. For more than a century it’s been worn by famous adventurers, explorers, movie stars and celebrities.

The rebound of Burberry from the lows of the late 1990s shows just how strong brands can be when they’re nurtured instead of exploited.

Of course, Burberry also has lots of very experienced and highly competent people, an existing base of stores, relationships with suppliers and so on, but these are small fry compared to the brand and its history.

One potentially valuable and hard-to-replicate asset that Burberry seems to miss is a culture of growing its leaders from within. The current CEO (who has just resigned) was flown in from outside the business.

Admittedly his predecessor, Christopher Bailey, did spend ten years at the firm as a designer. He eventually became Chief Creative Officer and in 2014, became joint CCO and CEO. This seemed like a potentially ego-driven stretch too far and by 2017-2018 Bailey was out.

Bailey's predecessor, Angela Ahrendts, also came straight in as CEO from outside Burberry and was chosen specifically to drive forward Burberry’s transformation in the mid-2000s.

So for most of the last 15 years, Burberry has had a variety of CEOs who were either external hires or seemingly inappropriate internal hires. This does not look like a company that has a culture of retaining the best talent by giving them a clear career path to the top. The current CFO also joined the company from the outside in 2017.

But perhaps with a brand as strong as Burberry, such trifling matters as retaining and nurturing the best operational talent are not so important? I doubt it.

Q.11. Does the company benefit from core market leadership?

YES - Although Burberry is by no means the global leader in luxury fashion or accessories, that doesn’t necessarily matter.

With strongly branded luxury products, people are willing to pay up to buy the brand, so economies of scale are not as important.

Where leadership does matter is that the company is the go-to brand for its core products.

Ferrari is the brand for supercars. Rolls-Royce is the brand for luxury cars. Rolex is the brand for luxury watches and Burberry is the brand for trench coats and British luxury fashion.

Q.12. Does the company benefit from switching costs?

NO - Customers can easily buy their luxury items from another fashion house, although if they want something with the Burberry label, there’s only one place in the world to get the real thing.

Is this company defensive?

D.1. Is the company’s core market defensive?

NO - Luxury brands, especially heritage brands rather than cutting-edge fashion brands, tend to do better during downturns than the clothing industry overall. So this does make Burberry somewhat defensive.

And in keeping with that view, Burberry has produced impressively consistent results for decades.

However, it is still a fashion retailer so that makes me less confident of its defensive credentials. Also, it’s moving towards luxury fashion and away from heritage luxury, which may make it less defensive in the future.

On that basis, I would rather categorise Burberry as a cyclical business, albeit a relatively defensive one.

D.2. Is the core market expected to grow over the next few decades?

YES - The luxury fashion market is expected to grow by around 3.5% per year until the end of 2025, which is broadly similar to the expected growth of the overall global economy.

Beyond that, I assume the luxury fashion market will continue to grow at a similar pace.

D.3. Is the core market relatively free from regulatory risk?

YES - Obviously the clothing market is regulated, but regulatory costs or the risk of abrupt regulatory shifts are not significant.

D.4. Is the core market unlikely to be disrupted?

YES - The market for luxury items isn’t likely to be disrupted anytime soon. Some people have lots of money and they like to spend it on expensive things, and that’s the way it’s always been and probably always will be.

What is being disrupted is the distribution channel through which people buy their luxury (and other) goods. The biggest shift, of course, is the move from real-world stores to online stores. This process is now quite long in the tooth, having started at least 20 years ago for most retailers.

Of the major luxury brands, Burberry is generally regarded as being somewhat ahead of the curve. Much of this has to do with Angela Ahrendts’ decision to go after millennials as they would become the company’s core customers in the decades ahead. “Go where the customers are” is an old business truism; millennials are usually online so that’s where Burberry went.

As Ahrendts said, “We needed to purify the brand message and how we were going to do that; by focusing on outerwear, by focusing on digital, by targeting a younger consumer”.

The company embedded digital into its marketing from the ground up and was an early adopter of social media marketing. There are lots of articles online about how well Burberry’s digital branding strategy has worked, e.g.

- How Burberry became the top digital luxury brand

- How Burberry is leveraging technology to lead in the digital age

Given that digital disruption in retail has been going on for 20 years and that Burberry seems to be a leader in digital, I don’t think disruption is a major issue.

D.5. Is the company free from significant concentration risk?

YES - Burberry isn’t heavily dependent on any one employee, customer or supplier, so concentration risk is low.

D.6. Is the company free from significant product or patent risk?

YES - Burberry’s revenues are spread across a large number of products, with no single product (even its trench coat) generating a significant amount of revenue (my definition of significant is more than 10%).

The company does have intellectual property but these are mostly trademarks that, unlike patents, don’t expire.

D.7. Is the company largely unaffected by commodity prices?

YES - Although Burberry obviously uses commodities like gas or oil, normal changes in their prices don’t have a material impact on the company’s results.

D.8. Does the company have prudent financial leverage?

YES - Despite Burberry’s position as a leader in digital retail, it still has over 400 directly operated stores and concessions, and most of these are leased. This, combined with debts taken on to smooth out the impacts of the pandemic, gives the company a debt and lease liability of almost £1.4 billion.

That’s about 4.7 times the company’s ten-year average earnings, which is pretty close to my limit of five for store-based retailers. Given Burberry’s relative defensiveness I don’t think this is excessive.

Note that usually, my debt limit for cyclical businesses is four times average earnings, but store-based retailers have most of their financial obligations as dozens or hundreds of leases, and that can be a more flexible arrangement than owing an equivalent amount to a handful of banks.

Is this company good value?

V.1. Is the company free from problems that are likely to materially damage its long-term prospects?

YES - The pandemic is the obvious big risk that’s on everyone’s minds at the moment. A year ago I thought the pandemic was unlikely to have a lasting negative impact on Burberry, and today I’m virtually certain it won’t have a lasting negative impact.

Burberry’s earnings did fall off a cliff in 2020 and it did suspend its dividend for a while, but that’s to be expected. In 2021, its revenues recovered almost to normal levels, it produced record earnings and the dividend was reinstated in full.

Barring a very bad variant, I don’t see anything that’s obviously going to stop Burberry from recovering fully and returning to relatively consistent growth.

I should add that the CEO is about to leave, and as I’ve already mentioned, Burberry doesn’t have a great recent track record of growing its own leadership. So the company will probably bring in another outsider, giving talented potential CEOs within the company more reason to leave.

Even so, I don’t see the changing of one CEO for another as a major risk. Or more accurately, it is a risk, so that’s why I look for companies where their quality comes from deep within rather than from whoever happens to be sitting in the hot seat at the moment.

V.2. Is dividend growth very likely over the next ten years and beyond (and how much)?

YES - I'm interested in how much Burberry's dividends are likely to grow over the long term because I value companies using something called a discounted dividend model.

Discounted dividend models are based on the idea that the value of an investment (such as a house or a company) is determined by the cash (i.e. the dividends) you can reasonably expect to get out of that investment over its remaining lifetime.

The present value of those future dividends is often called the intrinsic value of the company. That's because the valuation is based on factors that are intrinsic to the company (its revenues, earnings, dividends and so on) and not on extrinsic factors such as the opinions of other investors.

Turning back to Burberry, I think a conservative and realistic scenario is that the luxury fashion market will continue to grow as more people become affluent, and that will allow Burberry to continue growing over the long term.

Fortunately, my dividend model for Burberry is fairly simple. The only complication is that in the past Burberry occasionally returned large sums of cash to shareholders by buying back its shares.

This matters because I value companies as if I’m going to buy the whole thing. If I owned Burberry outright then it would make no sense to do buybacks because I would effectively be buying back shares from myself. It would generate nothing but broker fees.

So my dividend model assumes that Burberry will replace future buybacks with special dividends, and that shows up in the model as an increase in dividends from 2023 onwards.

Here’s my model of Burberry's future dividends followed by the underlying assumptions. If you're not familiar with these models I will explain all shortly:

Assumptions:

- Net return on capital (ROCE) in 2022 remains slightly subdued thanks to the pandemic.

- The 2022 dividend grows by 5%.

- Net ROCE returns to historically normal levels in 2023.

- Dividends increase significantly after 2023 as cash historically returned to shareholders through buybacks is instead returned as dividends. The dividend cover from 2023 is 1.4, which is equivalent to the historical average when buybacks are included.

- Long-term dividend growth is around 4%, reflecting the level of retained earnings available to fund growth, as well as Burberry's exposure to international markets and proven ability to expand its product suite either directly or through licensing deals.

You can find a blank template of this dividend model in my investment spreadsheet.

In Plain English, the table says I think it's both conservative and realistic to assume that Burberry's dividend will grow from 45p in 2022 to 96p in 2030, and beyond that, I assume the dividend will continue growing at almost 4% per year.

So if we purchased Burberry at £10.77 and if my dividend model is correct (which it won't be; hopefully reality will turn out even better) then those dividends would give us a 10% annualised rate of return. That's my target rate of return, so I call this my Buy Price.

And if we purchased Burberry at £21.50 and if my dividend model is correct then those dividends would give us a 7% annualised rate of return. The higher purchase price gives us a lower rate of return because the starting dividend yield is lower.

7% happens to be the UK market's average rate of return, so at £21.50 Burberry would give us the same expected return as the overall market. This is known as fair value. Since I'm after a better return than the market, I refer to fair value as my Sell Price because I'm usually looking to sell if the share price reaches fair value.

The Margin of Safety in the dividend model is a bit more complicated. It tells you where the current share price is between the buy and sell prices.

For example:

- If the margin of safety is 0% then the current price equals the sell price (fair value)

- If the margin of safety is 100% then the current price equals the buy price

- If the margin of safety is 50% then the current price is halfway between the buy and sell price

At the time of writing (early August 2021), Burberry's share price was £21.57. This is slightly above the sell price of £21.50, so there was no margin of safety in the price.

If reality turns out to be worse than the model assumes, then with no margin of safety the shares could end up producing below-market returns over the long term.

V.3. Are the risks and expected returns from this investment satisfactory?

NO - There is no doubt that Burberry is a company I would be happy to invest in.

In fact, I added Burberry to my model portfolio and personal portfolio in 2015 at a price of £13.70.

So far the investment has produced a total return of 8.2% annualised, which is below my target of 10% but better than the FTSE All-Share over the same period (beating the All-Share is a bare minimum target).

So I like Burberry, but the issue today is its share price.

At £21.57, Burberry has a dividend yield of around 2%. That’s low, especially as I'm aiming for something closer to 5% if I can get it. If we add in cash from Buybacks then the yield to shareholders increases to 3.5%, but that's still mediocre.

My model assumes that Burberry will grow by around 4% per year, giving a total expected return of 7.5% (3.5% from the expected 2022 dividend and 4% from growth). That's more or less the same as the UK market’s expected long-term return.

In other words, according to my dividend model, which I think is both conservative and realistic, Burberry is very close to fair value and therefore very close to my sell price.

I don't think Burberry is overvalued at £21.57. It just isn’t obviously undervalued.

My portfolio has quite a few considerably more attractively valued holdings than Burberry and that’s where I’d rather have my money invested.

Final Decision: Are you happy to own this company at this price?

NO - At £21.57, I don’t think Burberry is a terrible investment, but given the non-existent margin of safety, I’m happy to sell Burberry and reinvest the proceeds into one of the more attractive holdings in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio.

For the record, I sold Burberry on August 9th at £21.57 and I would happily invest in Burberry again at the right price.

I insist on a margin of safety of at least 50%, and currently, that means I would only consider reinvesting in Burberry if the price fell below £16.

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.