As a long-term dividend investor, there is a good chance that when I invest in a company, it will remain in my portfolio for years and perhaps even decades.

Given that I could be invested in a company over that sort of timeframe, I want to be reasonably sure that the companies I invest in will be as successful ten years from now as they are today, and hopefully with significantly larger revenues, earnings and dividends.

That's why my dividend investing strategy looks for companies that already have an impressive track record of consistent dividend payments, strong dividend growth, high profitability and low debts. However, I would never invest in a company just because it has an impressive financial track record.

Instead, I always go beyond the numbers, searching for companies with enduring core businesses and stable growth strategies that have been successfully battle-tested in the real world over decades, and exactly how I do that will be the topic of this blog post.

Table of contents

- Does the company have a focused core business?

- Has the company had the same core business for over a decade?

- Has it had the same growth strategy for over a decade?

- Does the company favour organic growth over acquisitions?

Does the company have a focused core business?

If a company is to survive and thrive over many decades, it must focus on what it can do better than its peers. And just as few people can become world champions in multiple sports, few companies can become world-class beyond a single relatively narrow niche. In other words, quality companies usually have a highly focused core business.

What is the company's business model?

I like to get the ball rolling by browsing through the company's website and latest annual report for about an hour or so. The idea is to build up a high-level understanding of what the company does to create value for its customers and profit for its shareholders. I'll finish up by writing a few paragraphs summarising what the company does.

After that, I'll read the business model section of the latest annual report and summarise that in a few paragraphs as well.

What are the company’s major divisions?

Most quality dividend stocks are mature businesses that are complicated enough to have multiple divisions, so the next step towards identifying the core business is to list out and describe the company's divisions.

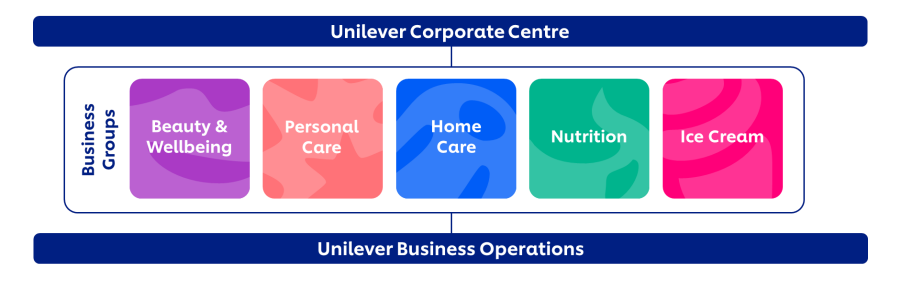

Most companies have an organisational structure that divides their operations into divisions based on product type or geography. For example, Unilever (which is currently a holding in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio) has five divisions, including Ice Cream and Beauty & Wellbeing, which are based on product type.

You'll find these divisions detailed on the company's website and in its annual reports. I usually start off by writing a few paragraphs about each division.

Some of the key questions I'm looking to answer for each division are:

- How much revenue and profit does it produce?

- Who are the core customers?

- What are the main products and services?

- What resources are required to produce the products and services?

- What activities are required to produce the products and services?

This looks like a lot of work, but it doesn't have to be. At this stage, the goal is just to begin to understand the business, so a sentence or three for each of those questions per division is usually enough.

If you're not sure what activities or resources are required to provide a particular product or service, just make an educated guess. Your knowledge about the company will grow as you work through the rest of the analysis, so you can always come back and extend and improve your answers at a later stage.

It can also be a good idea to look at the back of the latest annual report to see how the company breaks down its revenues and/or profits across different reporting segments. You'll often find revenues broken down by country, product type, brand or other segments, and making a note of these can also improve your understanding of a business.

Is there a focused core business?

After describing the company’s divisions, you should have a reasonably good idea of how the company works and, therefore, whether it has a focused core business.

For most companies, the core business is fairly obvious, but it isn’t always. If I’m not sure which divisions or competencies make up the core business, I find it helpful to ask:

Are there clear benefits to having these divisions under the same corporate roof, or would it make more sense to break them up to make two or more entirely separate companies?

If there is a clear rationale and strong benefits to having these divisions under the same roof, then I would consider them as part and parcel of the same core business. If it makes little or no sense to lump the divisions together, then I would say that the largest division (or group of closely related divisions) is the core business, and any unrelated divisions are little more than a corporate ball and chain (adding lots of weight but little value).

GSK is an obvious example, where some shareholders pushed for years to get the company's pharmaceutical and consumer healthcare divisions split into two separate businesses. Eventually, management gave in, and GSK was broken up in 2022.

Another example is RM, a small-cap stock providing goods and services to schools. About half of RM's business is like an Amazon for nurseries, selling all manner of physical products like toys, tables, chairs and so on. The other half is split between an IT services business and an online exam creation and marking business.

Those divisions share common customers (schools), but they have different products and different distribution channels that require different activities and resources.

I see no obvious reason to have those businesses under one roof other than the possibility of cross-selling multiple services to the same customer. However, there is a risk that any advantage would be more than offset by the additional complexity that comes with having three very different businesses operating under the same roof.

Here’s my rule of thumb for focused core businesses:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it has a focused core business that generates more than two-thirds of the company's revenues and profits

In RM’s case, the largest division (the Amazon for nurseries) generates about 55% of overall revenues, so in my opinion, it does not have a focused core business.

In contrast, Unilever has five product-focused divisions (Beauty & Wellbeing, Personal Care, Home Care, Nutrition and Ice Cream), but those divisions mostly make similar products from similar raw materials in similar factories and sell to similar customers through similar distribution channels.

Unilever may have five divisions, but the underlying core business is designing, making, selling and distributing non-durable consumer goods that tend to be liquids, solids or gasses in plastic or cardboard containers of one sort or another.

If a company does have a focused core business, the next step is to ask:

Has the company had the same core business for over a decade?

I may be invested in a company for ten or twenty years, so each company I invest in should have a core business that is very likely to grow over that timeframe. Unsurprisingly, one of the best ways to look for core businesses that will be enduringly successful in the future is to look for core businesses that have been enduringly successful in the past.

In other words, I want to filter out companies where the core business barely existed ten years ago or was acquired within the last decade.

Personally, I like to go all the way back to when a company was founded, so I can see the broad arc of its history from start-up to mature business. Most corporate websites have a history page, and that may have enough detail, but if not, then a quick search on the Web or Wikipedia should be enough to fill in any major gaps.

While the long history of most companies is interesting, what really matters is the last ten years, so that is where I focus most of my attention. I usually look at the company’s annual reports from five and ten years ago in order to compare and contrast them against the latest annual report. What I want to know is:

- Were the divisions broadly the same five and ten years ago?

- If they were different, are the differences just window dressing, or do they reflect a significant change in how the company makes money?

To answer these questions, I'll write brief notes describing the company's divisions as they were five and ten years ago. There will inevitably be differences, but are there fundamental differences?

For example, Unilever recently made significant changes to its organisational structure, moving from three divisions to a five-division structure supported by a lean Unilever Corporate Centre and with group-wide services (like HR and IT) supplied by Unilever Business Operations.

This was a substantial change, with Unilever's division now operating more like separate companies with shared resources. However, Unilever's underlying business remained unchanged.

If I look back ten years and find that today's core business either didn't exist or was merely a small non-core business a decade ago, then I will probably pull the plug and move on to another company.

Here’s my rule of thumb for core business longevity:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it’s had the same core business for at least ten years

If a company makes it this far, then I know it has an impressive set of financial results and a focused core business that has been in place for at least a decade. The next step is to ask:

Has it had the same growth strategy for over a decade?

Quality dividend stocks focus on long-term success by applying the same basic growth strategy to reach the same long-term goal over many years and even decades. What they don’t do is replace their growth strategy at the first sign of trouble or go chasing after The Next Big Thing.

And they are farsighted enough and sufficiently well-run that they don’t need to launch “transformation programmes” unless their market is disrupted in a way that was truly unforeseeable.

As before, the company's website and annual reports will contain the relevant information, so the first thing I'll do is summarise the company’s growth strategy from those sources.

For example, car insurer Admiral (another holding from the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio) defines its growth strategy as having three components:

- Accelerating towards Admiral 2.0: Apply cutting-edge technology throughout the business to reduce costs, standardise best practices, improve risk-pricing, improve customer service and so on.

- Diversification: Expand Admiral’s product offering beyond motor insurance to de-risk the business and to expand into markets where there is more room to grow (as Admiral already has a very large share of the UK motor insurance market).

- Evolution of motor: Prepare for the changing future of personal mobility and the rise of mobility subscription services and autonomous vehicles. Understand where the market could go and begin to develop capabilities that will be required to succeed in the decades ahead.

That is more or less how Admiral describes its strategy, but I would describe it slightly differently to emphasise the aspect I'm most interested in, which is:

Where is the company going, and how does it intend to get there?

In Admiral’s case, my answers would be:

Where is the company going?

- Admiral's stated purpose is to help more people look after their future

- To achieve that, it wants to be a global financial services business (which implies expansion beyond the UK and beyond insurance)

How does it intend to get there?

- Maintain and enhance the competitiveness of the existing business (through new technology, more data, better practices, etc.)

- Grow organically rather than through acquisitions

- Increase its share of existing markets (like UK motor) but not at the expense of strong profitability

- Expand overseas where possible (Admiral already has operations in France, Italy, Spain and the US)

- Expand into new products (Admiral has already expanded into home, pet and travel insurance, and more recently into personal loans)

This says more or less the same thing as the official version, but it's in a format that I can apply consistently across different companies to help me understand their direction of travel.

In Admiral's case, if things work out well, then I should expect the Admiral of 2033 to have a larger footprint in non-motor insurance products, a larger footprint in non-insurance financial products and a larger footprint outside the UK.

That is effectively a continuation of what the company has already been doing for the last 20 years or so, and that is exactly the type of growth strategy I'm looking for. In other words, I will take the consistent execution of a dull but effective strategy over the inconsistent execution of an ingenious strategy every single time.

If a company has to divert effort away from its growth strategy for several years in order to focus on fixing self-induced problems (usually known as a "transformation programme"), then that is a Red Flag that will stop my analysis in its tracks.

I realise that companies need to keep their heads down in order to get on with the daily grind of disciplined execution, but their leaders also have to have their eyes on the horizon, looking out for speed bumps and potholes that could knock them off course. Quality companies have the discipline to focus on the long-term as much as the short-term, whereas mediocre companies usually do not.

Bringing all of that together, here are my rules of thumb for strategic consistency:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its growth strategy has remained broadly unchanged over the last ten years

- Rule of thumb: Avoid a company if it went through a major transformation programme in the last ten years

If a company gets past all these checks, then it has an enduring core business that has been driven towards the same goal by the same growth strategy over many years.

The next step is to rule out companies where acquisitions have been a significant part of that growth strategy.

Does the company favour organic growth over acquisitions?

Some companies use the same core business and growth strategy over multiple decades, but their strategy is to grow by acquiring similar competitors, often with the explicit goal of dominating a fragmented market.

This is known as a roll-up, and it is an established and proven approach to generating impressive growth. The roll-up strategy has been used to build many market leaders, such as Compass Group (the world leader in outsourced catering services) and WPP (the world’s leading marketing business and another holding in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio). The result, in both cases, is a company made up of a smorgasbord of brands and businesses.

Rolling up an industry made these companies market leaders, which is good, but the roll-up strategy also tends to create a number of fairly predictable problems.

With so many different businesses brought under the same roof, roll-ups tend to have no consistent culture and few group-wide best practices. They use a multitude of incompatible IT systems, and they have many different suppliers providing the same resources, which reduces the group’s buying power.

Even worse, many of the acquired businesses may have spent decades trying to kill each other, so getting them to play nicely together can be an extremely arduous task.

In other words, although roll-ups often have market-leading scale, they also frequently resemble an incoherent and tangled mess of businesses that are often still competing against one another.

That doesn’t mean that I won’t invest in roll-ups (my portfolio currently holds at least five), but it does mean that I want all of the rolling-up to have been completed at least ten years ago. In my experience, ten years should be enough for a well-run roll-up to organise the sprawling mass of acquisitions into something approaching a finely tuned profit-making machine.

Avoiding bold acquisitions in unrelated industries

Rather than making numerous small acquisitions to roll up one part of one industry, some companies go to the other extreme and make a small number of very large acquisitions in order to expand into new markets or new industries.

I want to avoid those companies because large acquisitions in unfamiliar industries are a lot like a large meal of unfamiliar food. At the very least, they can cause serious indigestion, and at their worst, they can be deadly (especially if the food being eaten is past its sell-by date).

Roll-ups and "transformative" acquisitions are easy to spot because they’re usually paid for out of cash or by issuing new shares, both of which will be detailed in the company’s financial statements.

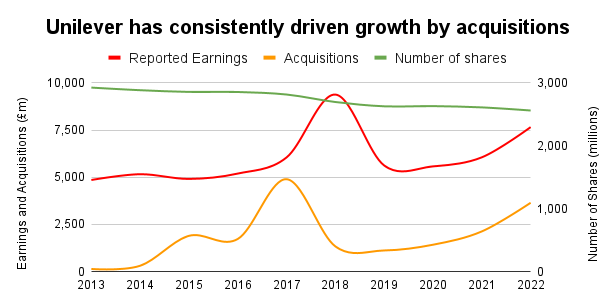

For example, one part of Unilever’s growth strategy involves the acquisition of other brands, which it then plugs into its global design, manufacturing, marketing and distribution machine to drive faster growth than those brands could have achieved as independent companies.

Here’s a chart showing Unilever’s reported earnings, cash spent on acquisitions and the total number of shares over the last ten years.

Data from SharePad

The chart shows that Unilever has indeed made acquisitions in every one of the last ten years. However, none of the acquisitions were large, as none exceeded Unilever's annual earnings, and none were significantly funded by issuing new shares (the total share count actually fell as a result of consistent share buybacks).

Here are my rules of thumb for the prudent use of acquisitions:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a roll-up if the roll-up phase was completed more than ten years ago

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it spent less on acquisitions than it made in profit over the last ten years

- Rule of thumb: Avoid a company if it made large acquisitions (costing more than an average year's profit) in non-core industries in the last ten years

Unilever passes all three tests because (1) although parts of Unilever could be described as roll-ups, any aggressive rolling-up was done decades ago, (2) it spent about £20bn on acquisitions over the last ten years versus total profits of £60bn and (3) most of those acquisitions were directly related to its core consumer goods business.

Conclusion

To summarise all of that, I would say that the gold standard for quality companies is that they have:

- Had the same core business for at least a decade

- Built that business organically rather than through acquisition (or built it through acquisitions decades ago)

- Had the same fundamental growth strategy for at least a decade

There is a risk that I'm over-emphasising consistency and stability at the expense of agility and adaptability. Of course, quality companies do need to change and adapt as the world around them changes, but their ability to innovate and adapt is built upon the solid foundation of an enduring core business and a stable growth strategy that barely changes from one decade to the next.

This combination of preserving the core while stimulating progress is a fundamental feature of quality companies, and it is something I look for in every potential investment.

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.