This blog post breaks down my dividend investing strategy into five basic steps.

If you're new to dividend investing and aren't sure if it's right for you, you should read this post first: The pros and cons of savings vs. dividends for retirement income.

The five steps to investing in dividend stocks:

- Step 0: Think like a business owner

- Step 1: Identify quality dividend stocks

- Step 2: Estimate fair value

- Step 3: Buy at a discount to fair value

- Step 4: Diversify wisely

- Step 5: Rebalance regularly

Step 0: Think like a business owner

Step zero is to think like a business owner. This isn't really a step at all; it's more of a philosophical bedrock that underpins the five steps.

If you've been investing for a while, thinking like a business owner may sound obvious, but for less experienced investors, it isn't.

For example, when I started investing in the mid-1990s, the only thing I knew about the stock market was what the evening news told me. And what the news told me was that the FTSE 100 had gone up or down a bit that day or that the share price of a big company had fallen because the company made a loss or had some bad publicity.

So, like most novice investors, my focus was on share prices and their movements from one day, week or month to the next.

Eventually, I learned that putting share price movements front and centre is a terrible idea because it ignores the fact that shareholders are business owners. And I mean that literally because if you own shares in Tesco, you literally own a piece of Tesco.

This is hugely important because thinking of yourself as a business owner should fundamentally change how you think about investing.

Business owners focus on the businesses they own

Let's say you win the lottery, and in a moment of madness, you buy Marks & Spencer outright. Now that you own M&S outright, what information would interest you? Would you spend most of your time worrying about the share price?

The answer is that you wouldn't because if you owned M&S outright, you would own all of its shares and there wouldn't be a share price (because prices only emerge when there are buyers and sellers, and if you own all the shares and aren't looking to sell, there is no seller to negotiate a price with).

If there is no share price to worry about, what would you focus on instead?

You would probably want to know things like:

-

How much revenue did M&S make last year? How much profit?

-

What is its strategy, and how is it progressing against that strategy?

-

What return is it getting on profits (that belong to you, the owner) retained within the business?

-

What are its competitors doing?

-

What are the prospects for its industry over the medium and longer term?

-

What profit and dividend growth can the company produce over the next ten years?

These business fundamentals are what business owners focus on because it's how they gauge the progress of the companies they own. These fundamentals also help business owners value their businesses, just in case someone wants to acquire the business from them (I'll have more to say about valuing companies in a later step).

As stock market investors, we are business investors. On that basis, almost all of our focus should be on the fundamentals of the businesses we are invested in rather than the short-term ups and downs of their share prices.

Step 1: Identify quality dividend stocks

If our focus is squarely on businesses, what sort of businesses should we invest in?

As a dividend investor, I want a good combination of dividend yield, dividend growth and capital gains, so I focus on quality companies that are likely to pay a rising dividend for at least the next ten years.

Not all companies can produce long-term sustainable dividend growth and those that do usually have two key features: quality and defensiveness.

Identifying high-quality companies

In a nutshell, quality companies have durable competitive advantages over their peers. These advantages allow them to consistently take market share or expand into new markets repeatedly over many decades.

You can find quality companies by asking the following questions:

(1) Has the company consistently produced strong profitability?

The acid test for quality companies is that they generate consistent profits and consistently high returns on capital, where "capital" is funding provided to the company by investors (in the form of shareholder equity), lenders (as loans) and landlords (as leased property). That capital is then used to fund offices, stores, warehouses, technology, vehicles and so on, and the aim, of course, is to generate attractive returns from those assets.

As a simple example, if a company buys a factory for £1 million and that factory produces a profit of £200k per year, then the £1 million of capital invested in the factory is making an annual return of 20%, which is good (it's a bit more complicated than that, but that's the general idea).

High profitability is essential as it allows quality companies to fund their growth with lower-risk retained profits rather than higher-risk debt. The best companies can fund consistent strong growth with little debt while paying a consistently growing dividend.

Related article: How to find quality companies with consistent profits and dividends

Related article: Find quality dividend stocks using these profitability ratios

(2) Has the company consistently produced inflation-beating growth?

As I just mentioned, quality companies produce high profits, which can be used to fund dividends and growth, so quality companies usually have long track records of relatively consistent growth across revenues (sales), earnings (profits), dividends and capital (buildings, machinery, inventory etc).

This growth often occurs when a quality company takes market share from weaker competitors or moves into adjacent markets closely related to its core business.

Related article: How to identify stocks with high-quality dividend growth

(3) Does the company have a focused core business?

If you want to win at the highest level in any sport, it will take a combination of talent and many years of specialist training. Winning in business is no different.

Quality companies that consistently win over time have, in most cases, spent decades focusing on a narrow set of capabilities, providing customers with a limited set of products and services.

So, if you're looking for a quality company, you should look for a business that has had the same narrowly focused core business for at least a decade.

Related article: How to find quality dividend stocks with enduring core businesses

(4) Does the company have a durable competitive advantage?

There are many different types of competitive advantage, but most quality companies have at least one of these advantages:

- Market dominance: It's often very hard to beat market leaders as they benefit from economies of scale and brand strength, both of which are useful for attracting both talented employees and customers.

- Brands or reputation: This includes (1) loved consumer brands, where customers choose the brand first and worry about price second, and (2) trusted suppliers of critical components, where the cost of a component failure is high (e.g. medical devices), so customers are willing to pay more to buy from a trusted supplier.

- Unique business model: Some companies benefit from a unique business model. Common examples include (1) vertical integration (such as a car insurer that also repairs cars) and (2) horizontal integration (such as a retailer that sells a broader range of goods than any of its competitors).

- Long-term focus: Some companies are able to ignore the pressures of short-term investors and focus on developing a business that can thrive over the long term, even if that hurts short-term results. These companies typically either have strong founder ownership or they're able to develop their own CEOs who put the company's long-term interests far ahead of their own.

- Network effects: This is where the functionality of a company's product or service improves as more customers use it. A good example would be Rightmove, which improves as more buyers and sellers use it (this often leads to monopoly-like market dominance).

- Switching costs: This is a weak competitive advantage, but it's still useful. Think of how hard it is to switch bank accounts or to move a business from one computer operating system to another. This is why Barclays and Microsoft have been around for a long time.

Identifying relatively defensive companies

A high-quality vase should be worth a lot of money, but if it's so fragile that the slightest touch causes it to crack, then it's likely to be in pieces and worthless by the time you get it to an auction.

The same can be said of quality companies. If a company is so fragile that it breaks when the economy hits a bump in the road, it probably isn't the right investment for a defensive dividend investor.

So, in addition to quality, I also look for companies that are relatively defensive by asking the following questions:

(1) Does the company operate in a defensive industry?

The most obvious form of defensiveness is that the company operates in a defensive industry. In other words, it operates in an industry that is relatively insensitive to economic ups and downs. Just think how bad the economy would have to be before you stopped buying toothpaste. On the other hand, if there's any sign that the economy may be slowing, it's very easy to not buy a new car or a new house.

Defensive industries are: Consumer Staples, Health Care, Telecommunications and Utilities

While I do favour defensive industry stocks, it can be very restrictive to only invest in them, so I'm willing to invest in cyclical stocks, but only if they meet the next two criteria.

(2) Does the company operate in growing markets?

Imagine a highly competitive, high-quality company operating in a market that is immune to economic ups and downs. That sounds great, but what if its core market is in long-term decline? Eventually, the shrinking market will cause the company to shrink, and that isn't what I'd call defensive.

Because of that, it's a good idea to focus on companies operating in markets with long-term growth potential.

(3) Is the company robust?

Like the vase I mentioned above, some companies are just fragile. This usually happens because they have too much debt, but there can be other reasons, such as a pension scheme that is too large, or perhaps they rely too heavily on a single client, supplier or superstar employee. Or perhaps they're exposed to abrupt technological or regulatory change.

Related: How to avoid dividend traps with excessive debts

Step 2: Estimate fair value

If we're going to invest in businesses, then we must have a credible opinion about what those companies are worth so we're less likely to overpay for them.

Unfortunately, a company can be worth different amounts to different investors, so there is no single "correct" valuation. However, there is a generally accepted concept of fair value or intrinsic value, which is the price where the investor expects to receive a fair return in line with the historical market average (about 7% per year, on average, in the UK).

There are many ways to estimate fair value, but the theoretically correct approach is to use a dividend discount model based on an estimate of the company's future dividends.

How companies derive their value from future dividends

Some people have a hard time believing that companies derive their value from dividends and other cash returns to shareholders, so here's a thought experiment:

Imagine we have two companies; Company A and Company B.

Company A will pay a dividend later this year and go bust the following year, at which point its share price will fall to zero.

Company B won't pay a dividend later this year and it will also go bust the following year and see its share price fall to zero.

Given that scenario, which company is more valuable today: Company A or Company B?

The answer is Company A because you'll receive a dividend before it goes bust. With Company B, you get nothing but stress and disappointment.

This tells us that a company gets its value from the cash it is expected to return to shareholders and from nowhere else.

Once we realise that a company's value comes from its future dividends, the next obvious question is, how large will those future dividends be?

We cannot know the future precisely, but we can make realistic and conservative estimates that are good enough to base investment decisions on.

Estimating fair value by building a discounted dividend model

Discounted dividend models are made up of two components: (1) An estimate of the company's future dividends and (2) a discount rate, which discounts (reduces) the present value of those dividends based on how far they are in the future (because a £100 dividend paid 10 years from now is less valuable than a £100 dividend paid today).

My approach to estimating future dividends is to treat a company like a savings account. For example:

- If a savings account has an interest rate of 10% and contains £100, it will pay interest of £10 this year

- If half of that interest (£5) is reinvested back into the account at the end of the year, it will contain £105 and pay interest of £10.50 the following year

- If half the interest is reinvested each year, the money in the account, the amount reinvested and the amount withdrawn will all keep growing by 5% every year

We can apply a similar model to companies, where capital is the amount in the “savings account”, net return on capital is the “interest rate”, reinvested earnings are (unsurprisingly) the amount reinvested and dividends are the amount withdrawn.

The resulting dividend model doesn't have to be complicated, so I'll often use two simple assumptions: (1) the company will continue to earn historically average net returns on capital, (2) it will retain enough earnings to fund a progressive dividend; (3) the company's long-term growth rate falls to less than 5% because no company can outgrow the global economy forever.

This simple dividend model sometimes needs to be tweaked to take other factors into account, but in many cases, the simple default is good enough.

Once we've estimated the company's future dividends, we can calculate their present value by discounting them using the market's long-term return, which is 7% per year in the UK.

A company's intrinsic or fair value comes from all its future dividends, so the last step is to calculate the sum of all those discounted dividends.

In addition, I like to calculate a good value estimate, which uses a higher discount rate. In my case, I would ideally like a 10% annualised return from each investment, so my good value estimate uses a 10% discount rate.

To help bring all of this to life, the table below shows my 2023 model for Unilever, which (at the time of writing) is a holding in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio.

The assumptions are (a) Unilever will continue to earn historically average returns on capital and (b) it will continue to pay out a historically average proportion of earnings to shareholders.

Remember, this isn't a prediction or model of what I think the future will look like, it's just a simple scenario based on a conservative and realistic set of assumptions.

Note: Unilever's 2023 dividend was 171 Euro cents, so the above model includes a big jump in dividends between 2023 and 2024. This reflects the fact that Unilever has historically returned cash to shareholders through dividends and regular buybacks, and the buybacks show up in the model as higher dividends.

This is obviously a more long-winded approach to valuing companies than simply looking at a stock's dividend yield or PE ratio. However, building dividend models is more than just a way to value companies; it's a process that forces you to think about a company's future prospects in a rigorous and quantifiable manner.

Related article: How to Value Shares with a Dividend Discount Model (this link goes to my old website, UK Value Investor)

Resources: You can see example dividend models and build your own in the Company Review Spreadsheet on the Free Resources page.

Step 3: Buy at a discount to fair value

Having estimated a company's fair value, the next step is to decide if the share price is low enough to make it an attractive investment.

If the share price is below fair value, we call that a discount to fair value. Buying shares when they're trading at a significant discount to fair value is important for two reasons. First, it provides a margin of safety in case our estimated fair value turns out to be too high. Second, the lower the price we pay, the higher our expected returns will be, so the bigger the discount the better.

This is where the old mantra of buy-low and sell-high comes in. If we buy low (relative to fair value), we can reduce risk and increase expected returns. Risk is reduced because buying low will give us a wider margin of safety, and expected returns are increased because the dividend yield will be higher (and there's also greater potential for an upward share price re-rating).

How big should this discount be? Here are my rules of thumb:

Rule of thumb: Only buy if the discount to fair value is at least 33% and ideally it should be above 50%

Rule of thumb: Continue to hold stocks if the discount falls into the 10% to 33% range

Rule of thumb: Look at selling holdings where the discount has fallen below 10%

Step 4: Diversify wisely

Once you've found a company that you like with a share price that you also like, the next question to ask is, how much of your portfolio should you invest?

You could put all of your money into that one company, but most people would (quite rightly) say that was extremely risky. Alternatively, you might decide to invest 1% into it. But what would be the point of that? If the share price doubled, your portfolio would increase in value by a mere 1%.

As with most things, there is a sensible middle ground that we can aim for.

Limit your maximum position size

The whole point of diversifying is to reduce risk, so the first thing to think about is how much risk you're willing to take with any one company. In other words, how much could you stomach losing if one of your investments went to zero?

In my case, if one of my investments went bust, then I would want the rest of the portfolio to be able to fully recover within one year, assuming it was a year of normal returns.

The UK stock market's average rate of return is 7% per year, so I wouldn't want to have more than 7% invested in any one company. In fact, I use a slightly more cautious rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Don't invest more than 6% into any one company

Having put a limit on the maximum size of any one holding, the next thing to think about is minimum position sizes.

Limit your minimum position size

Given that it takes time and effort to analyse and value companies, it's reasonable to expect each of our investments to pull its weight. If, for example, we have a 1% position in a particular company, a doubling of that company's share price will give us a capital gain of just 1%, which hardly seems worth the effort.

So, in addition to having a maximum position size, I also have a minimum position size:

- Rule of thumb: Have at least 2% in each position

With maximum and minimum position sizes of 6% and 2% (at least in my case), the average position is around 4%, so that's also my default or target position size.

- Rule of thumb: Open new positions at 4%

Choosing the number of holdings

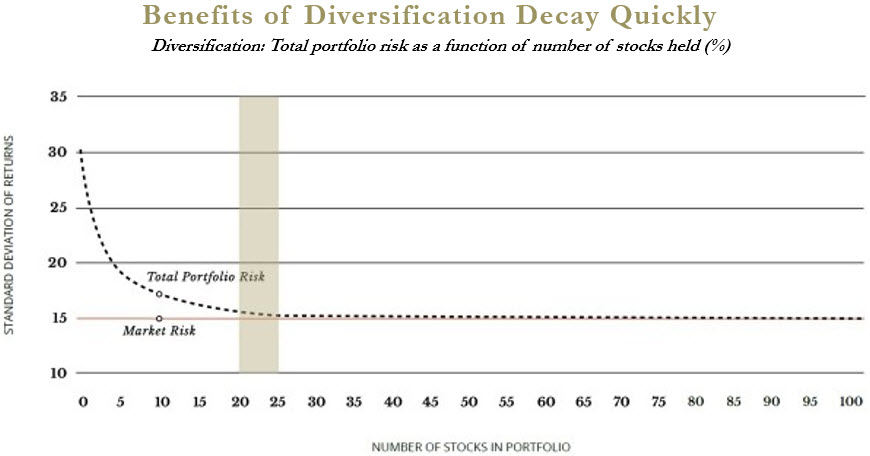

A 4% position size is 1/25th of the portfolio, so unsurprisingly, my rules of thumb will produce a portfolio with around 25 holdings. 25 holdings is a good number because it falls into the Goldilocks Zone between concentration and diversification for a portfolio of individual stocks.

Source: How Many Stocks Should You Own In Your Portfolio?

The problem with having a lot more than 25 holdings is that it doesn't meaningfully reduce risk, but it does reduce the expected return as you have to add in increasingly less attractive stocks.

Perhaps more importantly, owning a lot more than 25 stocks significantly increases the time and effort needed to stay up to date with your holdings.

- Rule of thumb: Optimise concentration and diversification by holding 20 to 25 companies

The next step towards wise diversification is to make sure we aren't over-invested in any one industry or sector

Diversify across industries and sectors

Investing in 20 to 25 companies is a good way to begin to diversify a portfolio, but if all of those holdings operate in the same industry, they'll be exposed to similar industry-related risks such as regulatory risk in the financial industry.

This is why most investors spread their investments across multiple industries, and we can take this a step further by spreading investments across multiple sectors within each industry, such as the Banks and Life Insurance sectors within the Financials industry.

- Rule of thumb: Don't have more than 20% of the portfolio's holdings in the same industry

- Rule of thumb: Don't have more than 10% of the portfolio's holdings in the same sector

Diversify across a wide range of countries

Another way to diversify your investments is to spread them across multiple countries. After all, nobody knows what the future has in store for the UK, the US, China or any other country.

Many companies in the FTSE All-Share generate much of their revenues overseas, so building an internationally diverse portfolio is relatively easy, even if you only invest in UK-listed companies.

- Rule of thumb: On average, holdings should generate less than 50% of their revenue from the UK (or any one country)

Step 5: Rebalance regularly

The final step on the journey to a well-managed portfolio of dividend stocks is to understand the power of rebalancing.

Perhaps the easiest way to understand rebalancing is to look at the classic 60/40 portfolio, which is 60% invested in equities and 40% in bonds.

If stocks have a fantastic year and bonds a terrible year, the portfolio could easily end up with an asset allocation split 80/20 between stocks and bonds. If that happens, the portfolio is no longer set up the way the investor wanted because it's far too heavily exposed to risky equities and underexposed to lower-risk bonds.

The simple answer is to rebalance the portfolio by selling some of the portfolio's equities and using the proceeds to top up the bond holdings.

This does two things. First, it brings the portfolio's expected risk/return profile back to target by bringing its asset allocation back to target. Second, and just as importantly, it automatically leads the investor to sell whichever investment has performed best (selling high) in order to top up whatever performed worst (buying low).

If rebalancing is carried out consistently over a number of years, it can have a meaningful impact in terms of both reducing risk and improving returns.

The good news is that rebalancing works just as well with a portfolio of quality dividend stocks.

As I've already mentioned, it's a good idea to have maximum and minimum position targets, and to top up undersized holdings and trim back oversized holdings. This is a simple but effective approach to rebalancing.

Rule of thumb: Rebalance holdings back to 4% when their position size reaches 6% or 2%

One final point is to be wary of repeatedly topping up the same holding. For example, if a 4% position falls to 2% you might top it back up to 4%. If it repeatedly halves in value you could end up repeatedly topping it up until you've invested far too much into that one stock. If it then goes bust, you'll lose the original investment and all of your top-ups.

Rule of thumb: Don't top up a holding if its cost size is above 6%

Note that cost size is the holding's position size using the cost of the shares (the total amount you've invested so far), not their market value. In most cases, the above rule will limit each investment to an initial 4% position and a single 2% top-up (if required).

That, you'll be glad to year, is the end of this fairly detailed overview of my dividend investing strategy. Hopefully, it contained at least one thing you found interesting or potentially useful.

If you'd like to learn more about this approach, visit the Free Resources page to see my full investment checklist and subscribe to the blog to read my latest company reviews and other articles.

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.